Shajar al-Durr – The King-Ransoming Sultan

The place is Egypt at the time of the Seventh Crusade. You have never heard of that one, you say? That might be because this week’s heroine stopped it before it could really begin by torching its ships Blackwater Bay-style and capturing its leader, the King of France. Her name is Shajar al-Durr and this is her story.

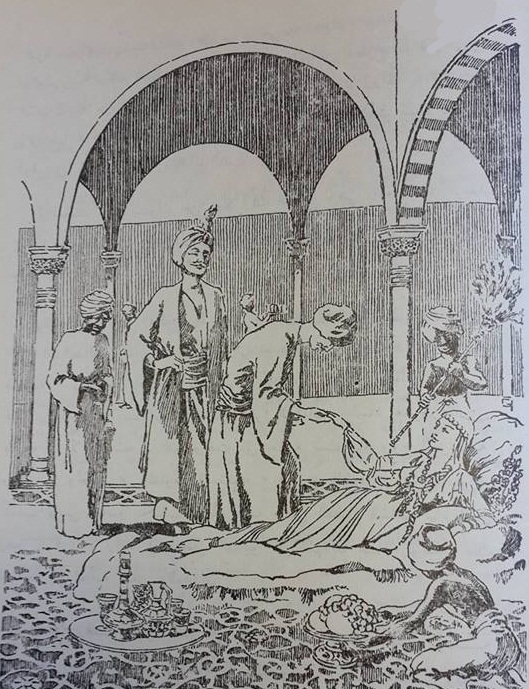

It begins with a lot of loose ends. She was presumably born around 1220 as a slave of maybe Armenian but most definitely Turkic descent. Her birth name is unknown. She must have been beautiful though, as she was bought as a gift to the son of the Egyptian Sultan and given the new name Shajar al-Durr, meaning String of Pearls. In 1240, when the old sultan died and his son succeeded him on the throne, she moved into the palace in Cairo with him. (It wasn’t quite that easy, but this is Shajar’s story, so I’ll keep it short here.) Not much later, she gave birth to their son Khalil and promptly the Sultan married her. For about eight years, their life was blissful. (The picture on the right is an illustration of her from a Lebanese book from 1966, but it might be set in these happy times.) Then, in 1249, the Sultan died, right when the 7th crusade, led by King Louis IX of France, knocked at the door. Well, they didn’t knock exactly, they sent a letter. It was not a diplomatic offer as one might expect, it was nothing but Louis detailing how he would crush Egypt under his foot.

Shajar, being a smart woman, only told the highest ranking and most trustworthy officers (exactly two people: the chief commander and the chief eunuch) of the predicament of the sultan being dead. In the true spirit of “The King is dead, long live the King,” they decided to hide the monarch’s death until the question of his succession was solved (Khalil was not the heir as he wasn’t the eldest son). So Shajar took the reins in the meantime, supported by her two accomplices. Luckily her husband had been kind of a lazy ruler, so there were many blank orders already signed in advance that were just waiting to be filled. And so they did. Shajar told everyone the Sultan was sick and needed rest to recover but was still watching over his country. And then she handed out orders like the badass she was. She even organized for food to be made for the Sultan and left in front of his door everyday for her to bring to him – or rather dispose of it. And so they convinced the people of Egypt that their leader was still alive.

The rumours that had existed in the beginning though reached the crusaders then and they were sure of their victory now. After all, their opponents didn’t have a king anymore. And in 1250 they launched their attack on the city of Al Mansurah where the Egyptian camp was stationed. They were delighted to see the city gates open, thinking they had caught the Heathens by surprise and expecting an easy victory. Once the army advanced though, they were ambushed and more than 15 000 soldiers and 400 Templars and noblemen were killed. Prior to the battle, Shajar had the crusaders’ ships set ablaze with Greek fire, so the expected crusader reinforcements never arrived. There were hostage taken as well. Amongst them King Louis IX.

Now for a fun interlude: this sparked the Shepherds’ Crusade of 1251, when a bunch of French farmers, peasants and, well, shepherds revolted and travelled to Egypt to rescue their king. I say they travelled to Egypt, but in fact they never made it there. The crusade dispersed rather quickly and soon they wreaked havoc on the French countryside.

So, now it gets a little complicated. There was the Sultan’s eldest son Turanshah, who was rightfully entitled to the throne and actually had been crowned before the Battle of Al Mansurah. But he made a couple of stupid mistakes. He drank in public (as a Muslim!) and rumours ensued that was mistreating his father’s household, specifically Shajar, who was beloved with her people. The biggest mistake of all however was replacing the Turkic military captains that had held command under his father and fought at Al Mansurah, with his own. Let’s say, they weren’t exactly happy to be demoted, so they stormed the palace while Turanshah was having a party. After receiving a sword blow to the hand, Turanshah fled but it was for nothing. They torched the tower he tried to hide in and finally shot him down (with arrows) in a riverbed. His reign was very short.

Instead the captains installed Shajar, with whom they shared a heritage, as sultan. This marks the beginning of a dynasty lasting more than 300 years, one where the Muslim servant class, the Mamluks, held the throne of Egypt. Since she had been filling in for her husband when he was away in battle, the court was used to her orders and accepted their new sultan (gladly I expect, with the domestic violence rumours from before.)

The people were favorable too, especially when she ransomed King Louis IX back to his own country for 400 000 livres tournois. To set this into perspective, that was about 30% of the country’s annual revenue. That’s a lot of money. And to repeat this once more: she was Sultan in her own right, supported by the military in a Muslim country in the 1250s. She also had her own coins made (see picture!)

Well, that didn’t last for too long. Even though she had her own coins printed and was acknowledged as sultan in her people’s prayers, there were still naysayers. Powerful naysayers that is. Firstly, news of the female sultan reached Syria and its leaders were not amused and attacked Egypt. The invaders were defeated but her country worried – more specifically her opposition in the country worried and in turn made the population worry. So with all this pressure, she agreed to marry Aybek, who had been the taste-tester/accountant of her late husband and had done admirable deeds in the battle against Syria. This meant Shajar had to step down in favour of her husband, which she did. And so her reign was arguably short as well.

Ayak wasn’t a good sultan. He didn’t have much of a backbone and was easily manipulated by all parties. It’s rumoured Shajar continued to rule from the shadows, but there is no proof. Another rumor was that she would not allow the marriage to be consummated and I wouldn’t blame her. You see, Ayak had a first wife who had born him a son and whom he refused to divorce. And then he talked about taking a third one! In 1257 Shajar finally snapped. She and her servants strangled him in the bath (or she had her servants do it, historians disagree.) And again she told everyone her husband was ill – although this time she actually admitted he was dead, albeit from an illness and not from a sudden lack of oxygen.

At first everything seemed fine, no one liked Ayak anyhow, but neither his first wife not the soldiers loyal to him believed her. And after a good torture, they had the confessions of the slaves involved. A palace revolt ensued. It isn’t exactly sure what started this riot, but it is likely that Ayak’s first wife had something to do with it. Anyhow, the angry mob found Shajar and beat her to death. With wooden shoes. Ouch. Then her half-naked corpse was dumped over the city wall into the moat where the rest of her (valuable) clothes were stolen by peasants. It was only three days later, after wild animals had already taken the one or another bite, that she was finally buried. Her final resting place is the Darih Shajarat al-Durr, a mausoleum she had built in 1250, located near the shrines of female deities. And although time has left its marks on the structure, the elaborate craftsmanship is clearly visible. (see picture)

Aybak’s son Ali became the new sultan, albeit only four two years. But the Mamluk dynasty that Shajar had founded lived on, even if she was omitted from the official list of sultans and sweeped under the rug for a good while. It is often hard to tell fact from fiction and there are many different opinions on almost everything in her story but they all agree in one thing: Shajar al-Durr was a badass woman who knew what she wanted and how to get it.

image credits:

sketch: from صلاح الدين الايوبي قصة الصراع بين الشرق و الغرب خلال القرنين الثاني عشر و الثالث عشر للميلاد from 1966 – via Wikimedia Commons

coins: from “A History Of Eypt” by Stanley Lane Poole, 1901 – Link

mausoleum: John A. and Caroline Williams on Archnet