Stephanie St. Clair – Harlem’s Queen of Numbers

In light of the current protests going on, today’s article is about a woman who was a community organizer and activist for black rights in America during Prohibition, as well as a successful gangster/businesswoman that stood up to the Mafia and the corrupt police system. Did I mention she was an immigrant too? Making a living as a black woman wasn’t easy from the get go, but not only did she build her own business and defended it for years, but continued fighting for a better chance in life for her community as well as those who came after her. Meet Stephanie St. Clair, Harlem’s Queen of Numbers.

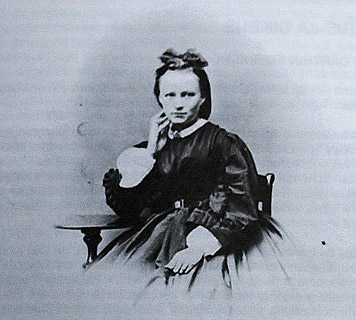

From what we know about Stephanie’s childhood, she was born in Le Moule, Guadeloupe on Christmas Eve 1897. Some biographers cite her year of birth as 1887 – a whole decade earlier – however the best researched source, a book by Shirley Stewart, is certain of the one I went with in the first place. However it is interesting that there would be a dispute about this as she was a well-educated woman and would have known her birthday …unless she wanted this confusion. You’ll see why that’s more than likely in a moment.

So, Stephanie was born mixed, French and African, and grew up with her single mother who worked hard to ensure a good education for her daughter. That way she learned her native French as well as English – in reading and writing as well as speaking, although some biographers state she learned the latter only when she was already in the US. In 1911, when she was 13 years old, Stephanie left her home on a steamboat for America. Arriving in New York the same year, she initially passed through and worked as a domestic servant before returning to the US five years later. The biographies aging her a decade state she spent time in Marseilles, France, before coming to the US, however this claim has been disputed by Stewart. Stephanie herself never disputed this claim though and speaking French, had no problem passing it as truth. And doesn’t it sound glamorous? And Stephanie was all about glamour for sure.

Whichever way she went, it is certain that she eventually settled in Harlem, New York, fitting right in with the growing African-American community. Arriving just a few years before the Great Migration when millions of black people fled the confederate South to settle in more liberal cities like New York. So the city was her playground, and it didn’t take long until she had her own gang: The 40 Thieves. Her main goal was to make a bunch of money fast and coercion and scams really seemed to work. By 1923 she was able to invest $10.000 to develop a numbers racket. The start of a lucrative career.

A short interlude to tell you about numbers rackets in case you’re as confused as I was. Other names for it are policy banking or just numbers game. It’s basically a mix of lottery, gambling and investment where the person betting had to guess three numbers to win after paying a fee to enter the draw. There were different ways on how these random numbers were “generated” and I don’t know which one Stephanie used, but the winner was determined the day after the bets were placed. While the practice was illegal, it was one of the few opportunities for the working class to invest their money and it was even more important to the African-American community. You see, at the time there were very few banks accepting black customers, so the policy banking was more or less their only investment option. While, yes, it certainly wasn’t the most honest of professions, it did provide the black community with a surprising amount of wealth and jobs.

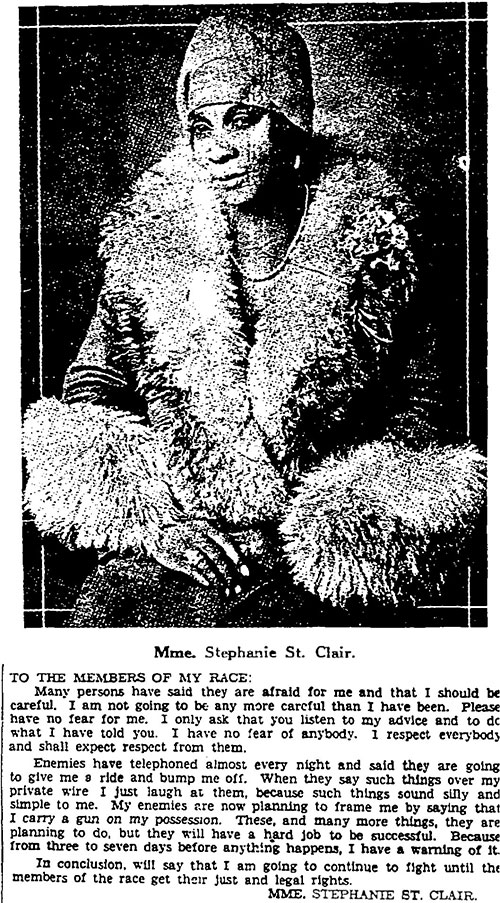

But back to our story. Stephanie teamed up with another famous black gangster called Bumpy Johnson and, making him her lieutenant, her business bloomed. For the next few years Madam St. Clair ruled the numbers rackets in Harlem, becoming rich herself but also giving back to the community. She paid her workers well and funded projects to help immigrants like herself to not only learn English but also give them a network and a sense of belonging. One of her main strategies was to put out newspaper ads – full-page and often with a big photo of herself attached – educating her community on their rights, advocating for voting rights and protesting police violence as well as the corrupt legal system.

You see, she was quite and extravagant person with an eccentric, opulent fashion sense and well-respected by the Harlem residents who were the first to call her Madam. Others called her Queenie. While contemporaries describe her as sophisticated and educated, she was also arrogant and known for her temper and occasionally foul mouth (in several languages!) It was that particular mix of character traits that make her story so interesting though. Like that one time she was arrested for her ads, publicized the trial and right after she was released after eight months of prison, she went to the higher ups, not only telling them how she had bribed officers but also how many of them were actually customers of hers. Many officers were fired that day. The Queen lived a lavish lifestyle and, earning an annual income of about $200.000, she amassed a small “personal fortune around $500,000 cash and [owned] several apartment houses.” She resided at 409 Edgecombe Ave in Sugar Hill, a renowned address of the Harlem Renaissance, alongside more reputable black citizens. Still she never made a secret of her occupation and nonetheless remained a major figure in her community. And she loved it.

With the Great Depression in 1930 and the end of Prohibition two years later, the (predominantly white) Mafia in the surrounding areas saw their profits dwindle and decided that Harlem would be a pretty good addition to their turf. One mobster in particular was determined to take over Madam St. Clair’s business: Dutch Schultz, a brutal man with a violent temper who would become her arch nemesis for the years to come. And he wasn’t subtle about his entrance. He would beat up and straight up kill numbers operators who refused to pay for protection. And when Madam St. Clair refused, he started a personal vendetta against her, threatening her via phone, kidnapping and killing her men and bribing the police wherever he could. He even got her arrested at one point! She responded in the same fashion, killing his men, destroying his businesses, tipping off the police and having his property raided by the police. One such raid cost him $12 million (which would be around $172 million today!) Then she wrote about it in her newspaper ads, because that’s just how extra she was. You might think that’s a pretty stupid move, but actually she used her writings as insurance against potential attacks on her life. By recording the threats against her in the paper, everyone would know who to turn to should something happen to her. Still it was a bloody war with at least 40 people dead.

Slowly this feud pushed Queenie out of the game though. With the police’s eyes constantly on her, she had to watch her every move. In the mid-30s she turned most of the business over to Bumpy Johnson who in turn protected her. And again she used the newspaper to her advantage, this time posting ads that catalogued her activities as a defense against any criminal charges. And for that she had to keep her nose clean. Ironically it was then that the fight against Schultz finally ended …with him being shot. It was a Mafia thing and Madam St. Clair had nothing to do with the assassination whatsoever but she couldn’t miss the chance for one last taunt. It was only a small bible verse that arrived on his deathbed in the hospital via telegram: “As ye sow, so shall ye reap.” It was signed “Madam Queen of Policy.”

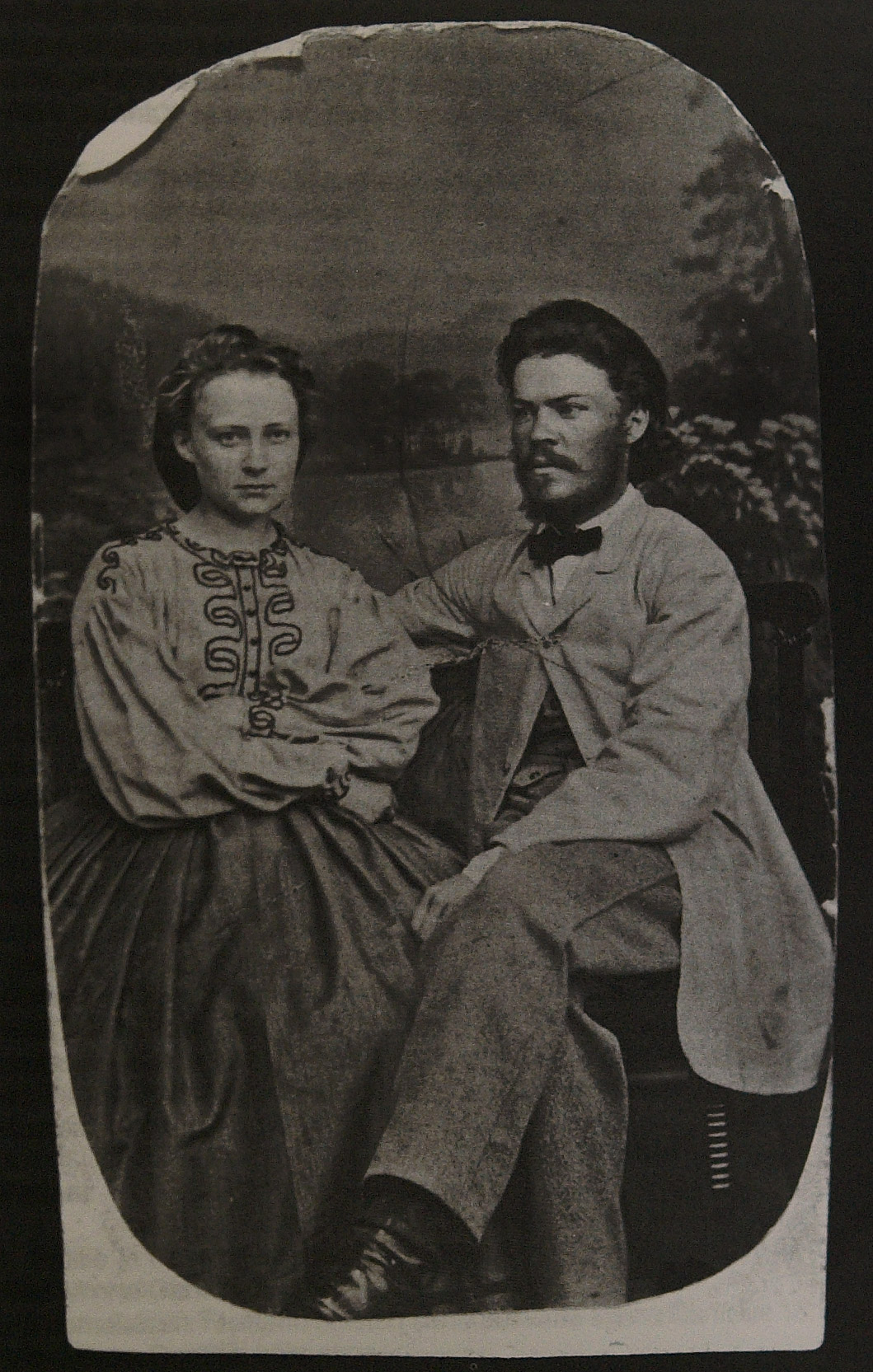

But even with Dutch out of the way, Madam Queen retired from the numbers game and instead focussed all her energy on her activism. She also met and married Sufi Abdul Hamid around 1936, an eccentric activist who ran a mosque as well. He was also very anti-semitic and because of this (and the fact that he was often seen wearing a Nazi-style shirt combined with a cape and turban) he was dubbed Black Hitler by the press. Madam St. Clair and Abdul Hamid were certainly a match in regards to their eccentric characters and flamboyant fashion, as well as their fight for black rights. However their marriage was a stormy one from the start and ended abruptly in 1938 when she shot him.

…or at him anyway. Abdul survived and went on to marry his mistress, a black fortune teller who went with the name Fu Futtam and somehow claimed to be Asian. The couple had already tried to establish quite a few businesses with Stephanie’s money and at some point she snapped. What followed was a sensational trial of Madame St. Claire vs. Abdul Hamid.

Throughout it all she maintained that “if [she] had wanted him dead, he would be dead.” Eventually her lawyers got him to admit that his name was actually Eugene, that he wasn’t from Egypt but from Philadelphia as well as tell them all about his affair. Still, in the end Madame St. Clair was found guilty by the all-white jury and sentenced to prison.

The duration of her stay there isn’t completely certain and ranges from 2-10 years and her trail gets a little faint afterwards. Just like with Dutch Schultz, fate seems to have had a strong dislike for those giving her trouble: just a few months into her imprisonment, Abdul Hamid died in a plane crash. After her release in the early 1940s it seems that she steered clear of criminal enterprises and once again fully focussed on her activist work. Continuing to use her newspaper ads, she publicized the discrimination against black people in her community as well as police brutality and the often illegal tactics employed in the name of justice. She kept campaigning for black voting rights and educating her peers on their civil rights until she died in 1969, quietly and still rich, shortly before turning 73. Four years earlier, in 1965, the Voting Rights Act had been passed which finally gave black people equal voting rights.

Stephanie St. Clair was a complex and fascinating woman, shifting between gangster and community advocate as she pleased. But this duality is what makes her so interesting, we can see her motivated by a genuine wish for socio-political advancement just as easily as by the desire for riches and publicity. She was in the middle of a fight against racial inequality and she wasn’t afraid to get her hands dirty. Her style of activism shaped future generations and shows just how creative especially marginalized groups can get when it comes to advocacy. Especially in these days her story is so important as it shows how exposing injustices and educating the community matters. It also shows that informal (and, let’s be honest, often illegal) networks are essential in organizing a successful protest against a corrupt system. So let’s learn from this incredibly smart woman and let’s make sure to continue her fight against police brutality.

image credits:

1: Photo of Stephanie St. Clair in her youth. Book cover of “Madame St-Clair, Reine de Harlem” by Raphaël Confiant – via Wikimedia Commons – Link

2: Harlem Numbers Banker Madame Stephanie St. Clair. (Courtesy of Morgan and Marvin Smith Photographic Collection, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture New York Public Library) – via the African American Intellectual History Society – Link

3: one of Stephanie St. Clair’s newspaper ads in The Amsterdam News – via Rejected Princesses – Link

4: African-American religious and labor leader, Sufi Abdul Hamid with his wife, Harlem mob boss, Stephanie Saint-Clair, in formal dress, January 23, 1938. (Photo by Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images) – embedded – Link

5: “Stephanie St. Clair Hamid in Custody” (fair use image) – via BlackPast.org – Link