Minna Canth – Finland’s First Feminist

Because it’s my Mum’s birthday, I want to honor another badass mother today. After her husband died, she raised their seven(!) kids by herself and even found time to not only manage the family store, but also fight for gender equality, writing text that were way ahead of her time. Let me introduce you to Minna Canth.

We’re in Tampere, Finland in Spring 1844 and a after their first son had died in infancy, textile worker Gustav Johnsson and his wife Ulrika were overjoyed when their daughter Ulrika Wilhelmina, or Minna for short, was born. In 1850 another boy would follow and two years later another girl. One year after her little sister was born, her father was promoted to managing a yarn store and the whole family moved to Kuopio. Even before that she had attended the school at the factory her father worked for and continued her education in her new home. The shop was so successful under her father’s management that Minna was even admitted to an upper class school!

That meant she was able to get a much better education than most working-class women at the time, not only learning the basics of reading and writing, but also history and geography and mathematics! Besides the main language, Swedish, she also learned to speak German, French and Russian, while at home she spoke Finnish. (Back then Swedish was the official language of Finland and it wasn’t until 1923 that Finnish was recognized in the same way.) Half the day was put aside for crafts – of course, it was a women’s school – but Minna really didn’t have the patience for that, she’d much rather devour every book she could find.

When a school to train female teachers was established in a city near her home, 19 year old Minna was among the first to apply. The Jyväskylä Teacher Seminary was the first school in Finland to make higher education accessible for women and of course Minna wanted in. And she got in.

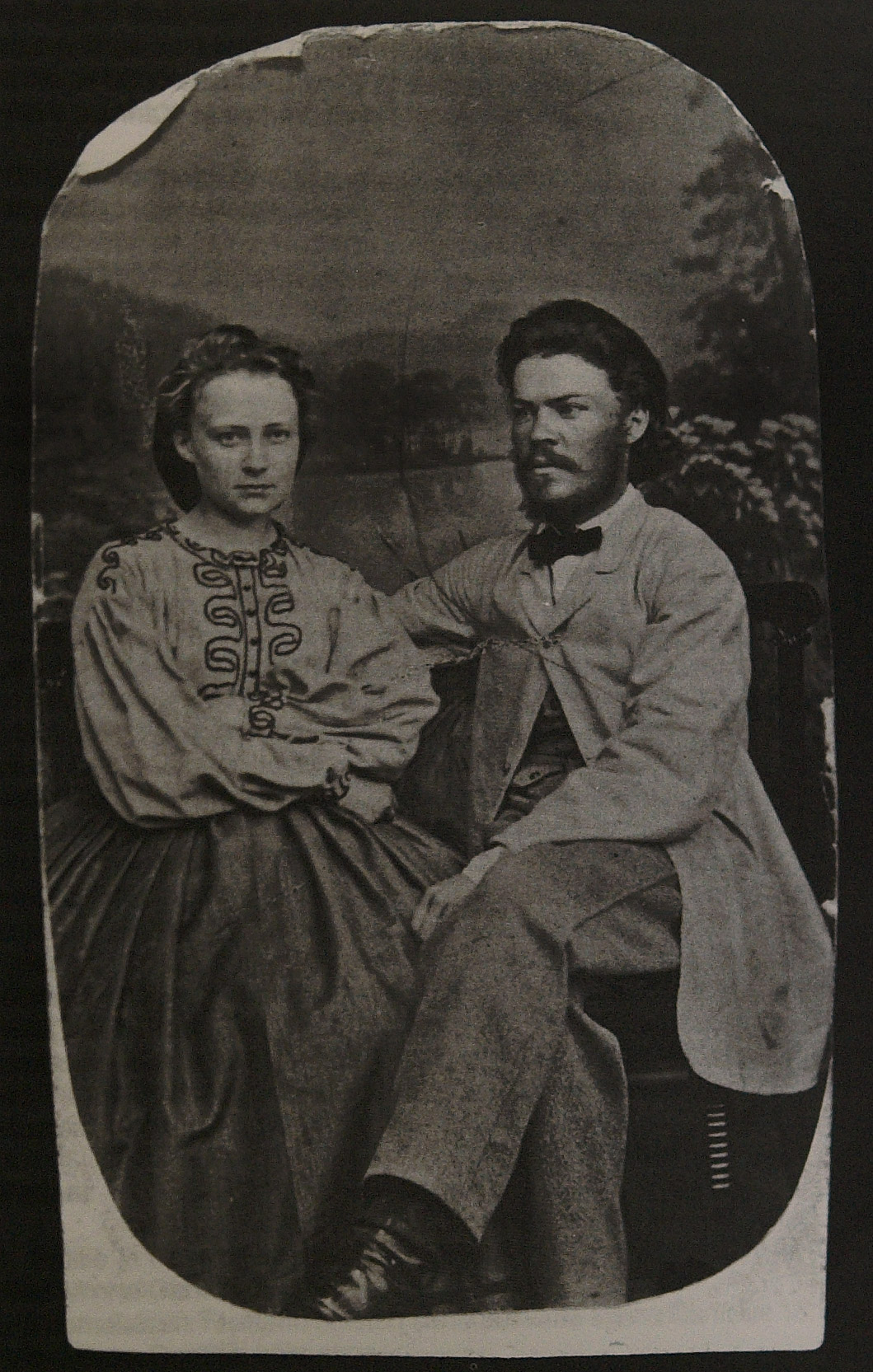

In 1963 she began her education as a primary school teacher and she absolutely loved it! Not only was she elated to keep learning, but she also loved the philosophy of teaching and unexpectedly enjoyed the hour of gymnastics everyday and regular outdoor activity. In her journals she wrote: “Here, even the careless, like me, are forced to take better care of their health” and the habit of daily exercise and long walks would accompany her throughout her life. Minna also found love somewhere unexpected: in her natural science teacher Johan Ferdinand Canth. And in 1965 the two of them married. Unfortunately that also meant that she wasn’t allowed to continue her education at the Teacher Seminary, as married women weren’t allowed to study at the time.

Even though her formal years of education were over, Minna had learned a lot and began to see society – and especially the role of women within it – in a whole new light. But for now she fully immersed herself in married life, taking care of the household while her husband worked at the school and as a newspaper editor. Her joy and pride was tending to the garden where she grew vegetables that not only fed her family but also produced a bit of income at the side. Apparently Minna had inherited her father’s talent as a salesperson. But not only her garden grew, her family did too. Between 1866 and 1890 the Canths had seven children!

Somehow in 1974 Minna found the time to start writing for the newspaper her husband worked at, focussing on women’s issues. She was incredibly happy to finally have intellectual stimulation in her life again, or as she called it “spiritual nourishment.” Her articles didn’t go over with the editors however and both her and her husband had to leave the paper only two years later. They were both immediately hired by the competition though and Minna began publishing her first fiction stories. They were even collected in a book in 1878!

But the happy family life came to a screeching halt when Johan Canth died unexpectedly in July 1879, leaving Minna alone with six children and a seventh on the way. Not only was she now a widow at 35, she was also really really broke.

She knew that continuing to write only newspaper articles would not sustain a large family like hers for long, so she thought bigger and sent a play to the Finnish National Theater in Helsinki where it was enthusiastically accepted. This would lead to a lifelong partnership with the director of the institution who taught her much. Still Minna knew it would be hard staying in the big city and after her youngest daughter Lyyli was born, she sold the family home in Jyväskylä and took her children on a three-day journey back to her hometown, Kuopio.

Returning home after 17 years of absence, Minna lost no time. Her parents had opened their own draper’s shop, but her father had died shortly after and now it wasn’t doing too well. So Minna took charge. Soon she had turned business around and was earning enough to not only take care of her seven kids and the family cat, but her mother and ailing brother as well. After her brother’s death in 1884, she took over his general store as well and she seems to have had a real talent for business: in 1895 she was elected as the first woman to be a voting representative in the General Merchant Meeting. There wouldn’t be another woman of a similar rank for the next 100 years. She also greatly enjoyed the freedom her existence as a businesswoman granted her. She made enough to hire people and finally, finally she had the time to write again!

Her home in Kuopio quickly became a meeting point for intellectuals and creative to discuss new ideas and Minna established a women’s circle to discuss social issues and needed reforms. But she didn’t just keep her ideas in her home, she wrote articles focussing on social and gender inequality for different newspapers and even planned a women’s magazine for which she ended up being too busy. Even if Swedish was the official language and she did speak it well, Minna made the choice to write in Finnish. Not only the language was unusual, but her opinions were often controversial and way ahead of her time as well – her topics included the wealth divide, public education, sexual repression and morality, as well as the stigma against sick and disabled people.

Often the deeper meaning of her work was overlooked in order to criticize the imperfect but very human characters and progressive ideas; some of her works were even banned! In 1889 she started a newspaper where she translated texts from all over Europe to debate international ideas with her readers, but that too was censored after just one year. She knew that she was ahead of her time – “a woman of a completely new age,” she called it – but she never gave up trying to usher in that new age for everyone else.

And she had her personal reasons to keep standing up to against the system. As her daughters grew older she once again realized how difficult it was for a woman to get a good education. Without further ado she hired high school boys to teach her daughters what they learned, like mathematics and Latin, in addition to their regular lessons at the girls’ school. Of course Minna didn’t just stop at that. She and some members of her women’s group saw the need for women’s education and In 1886 the first Finnish-language co-educational school in the country was established – all paid for via fundraisers! One of her daughters, Elli, followed her mother as an intellectual, even going to Switzerland for a few years to study natural medicine. I imagine that must have made Minna very happy, as she firmly believed that to achieve true gender equality, we must empower our young women, not only by educating them but also by teaching them to navigate the world outside the home without relying on a husband.

And we know that at least with Elli she did a great job in doing so for her own daughters. When Minna died in 1897, at age 53, Elli and her brother Jussi continued their mother’s businesses and they kept operating (under various names) until 1974! But Minna’s story is not completely over yet. Ten years after her death, Finland became the first European country to give women the right to vote. It is not unlikely that her writings had at least a little influence on that progress.

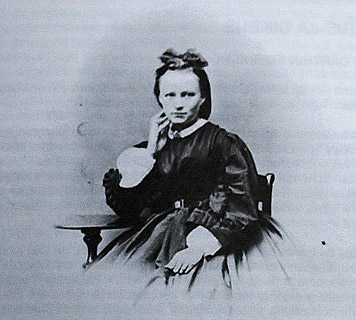

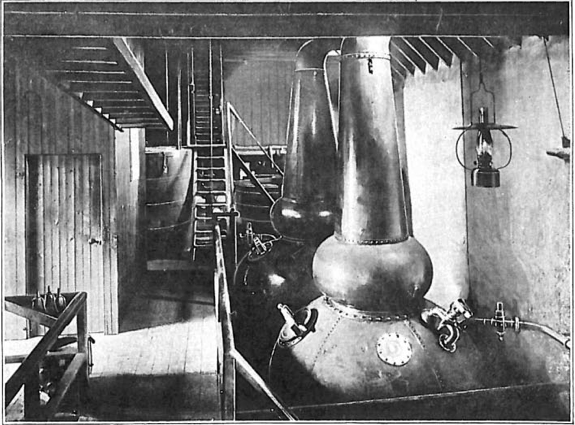

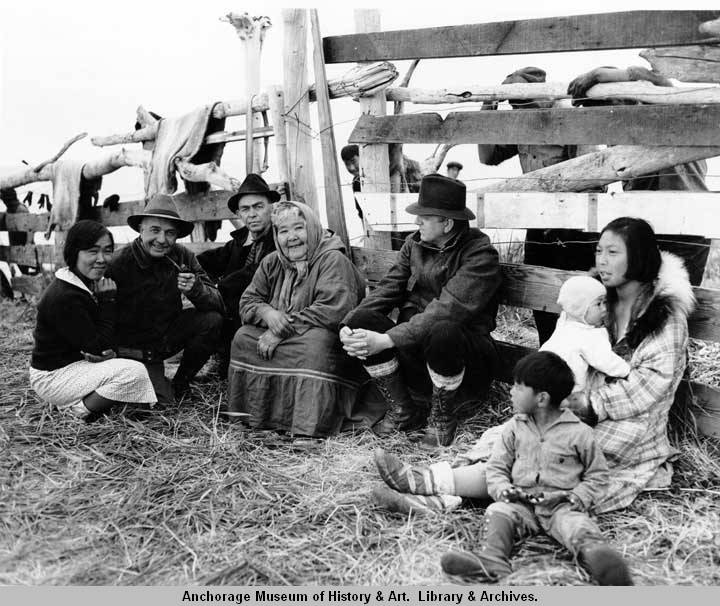

image credits:

1: “Finnish author Minna Canth (1844-1897) in her youth (age 13-16)” from her biography “Monisärmäinen Minna Canth : kirjoituksia hänestä ja hänen tuotannostaan” by Liisi Huhtala, 1998 – via Wikimedia Commons – Link

2: “Finnish author Minna Canth (1844-1897) and lecturer (teacher) Johan Ferdinand Canth (1835–1879) in Jyväskylä” from the biography by Liisi Huhtala, mentioned above – via Wikimedia Commons – Link

3: “One of the first uses of photographs in Finnish newspapers – Uusi Kuvalehti, June 1891, published in Kuopio – In picture: Kuopio-based authors Minna Canth and Juhani Aho” – from the biography by Liisi Huhtala, mentioned above – via Wikimedia Commons – Link

4: “Landscape from the cathedral tower” – Kuopio between 1889 and 1893, Minna Canth’s house is the light one at the corner. Photo: Aug. Schuffert [cropped] – Link

5: “Screw game in Kanttila [Minna Canth’s house in Kuopio]” – Pictured are Hanna Levander (left), Alma Tervo, Maiju Canth and Minna Canth, between 1890 and 1896. Photographer unknown – Digitized at the Kuopio Museum of Cultural History – Link

6: “Finnish author Minna Canth (1844-1897)” – date and photographer unknown – via Wikipedia Commons – Link