Helen and Elizabeth Cumming – Women Behind the Whisky

Today I’ll introduce you to not only one but two extraordinary Scotswomen who founded a whisky distillery that still exists today – and they did it illegally!

You see, in 18th century Scotland, the taxes on whisky were raised and raised as the English tried to control Scottish production. The laws honestly got pretty confusing and no distillery was charged at the same rate – and for most the taxes became unmanageable. By the end of the century there was a flourishing black market and illicit distilleries thrived. And one of them was spearheaded by our heroines for this week: Helen and Elizabeth Cumming.

Our story begins in 1811 when 34-year-old Helen and her husband John leased a small farm in on Mannoch Hill, above the River Spey in Scotland. They named their new home Cardow and, like many of their neighbors, set up an illicit distillery. While John worked the farm, Helen took care of the household and the whisky. Not only did she work the stills, the first recorded woman to do so, she was also responsible for the product’s distribution.

And so she would walk the 20 miles or so to the nearest township of Eglin, whisky skins hidden underneath her skirts, and sell them on the streets to whoever was interested. She also sold bottles of her whisky through the window of her farmhouse to whoever passed by. To avoid detection by the authorities, she developed a pretty smart scheme: Whenever officials were approaching her hometown she would disguise the distillery as a bakery and invite them in for tea. As there was no inn in the area, she would invite them to stay the night as well and while they were busy stuffing their faces, Helen would go into the back yard and raise a red flag or hung her laundry for all her neighbors to see, warning them to hide their whisky production as well. And even though John was convicted three times over the next five years, business never halted and soon the Cummings had earned a reputation for their high quality single malt. It wasn’t only their business that flourished, their family did too and before long there were eight children out and about – although some of them were likely born before they moved to Cardow.

Finally in 1824 taxes were lowered and one of the first people to purchase an official distilling license was Mr. John Cumming. Their eldest son Lewis had established a network of contacts already and helped Helen expand their distribution. It was also Lewis who had married our second heroine, Elizabeth, at some point and the young woman got involved with the family business almost immediately. She possessed a quick mind and an understanding for numbers and in the following years they grew their reputation; despite being the country’s smallest distillery they became quite well known.

In 1846 John died, leaving the brewery to his son. Yes, John was the official owner, not Helen, as married women still were not allowed to own property and her late husband had left it to their son. It was a wise decision though, Elizabeth and Lewis were an amazing team and soon doubled their output, meeting the increasing demand. By 1854 their business went so well that they had to employ two more people and couldn’t maintain their farm year-round, starting seasonal work. Now the fields were only worked during the summer while the other seasons were reserved for whisky-making.

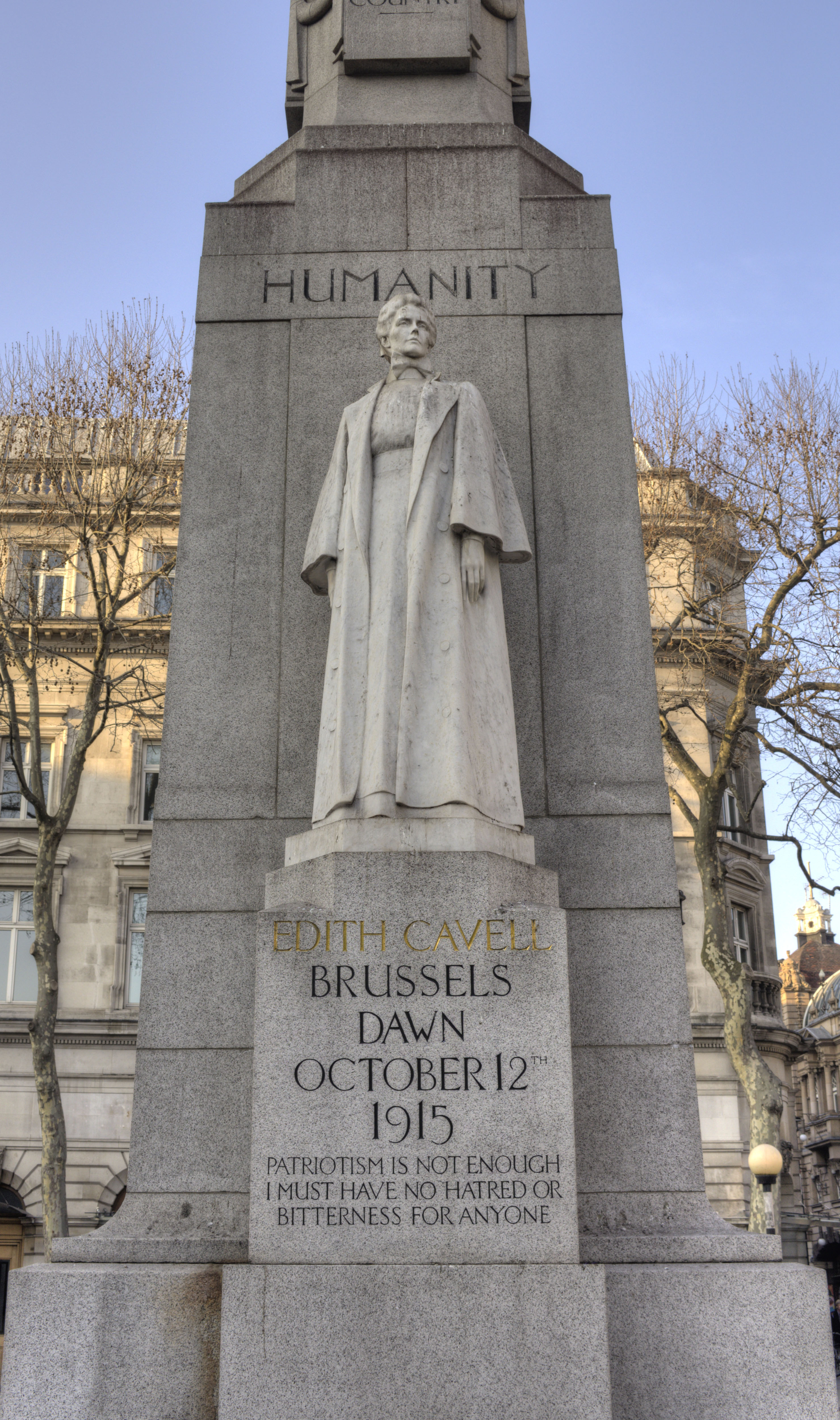

The news came that the new Strathspey railway was being built, a promise to increase business even more. What a disappointment it was when it was finally finished but the nearest station was four miles away from their home, connected only through poor roads. Then in 1872 Lewis died prematurely, leaving his mother, wife and their four children behind. But that didn’t get Elizabeth down; she took over the distillery and registered their single malt under the trademark Car-Dhu, meaning “Black Rock.” It was a total success. Unfortunately it wasn’t over with deaths in the family. After continuously working in the family business for more than fifty years, Helen passed away in 1874 only three years short of her 100th birthday. She lived to see her eight children grow up and met all of her 56 grandkids.

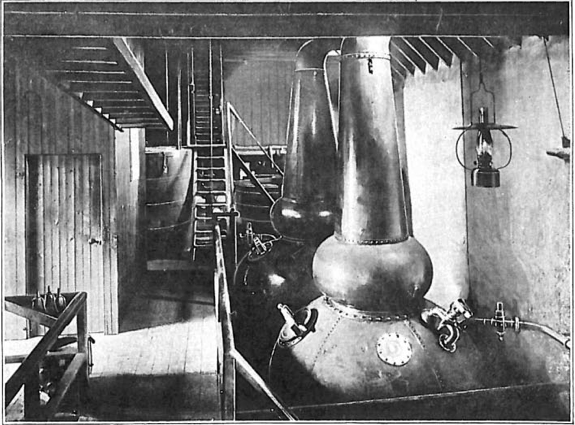

Under Elizabeth’s management the production grew steadily but still by 1884 she could’t meet the high demand for her product anymore. Promptly she bought four acres of land in the neighborhood and moved the business to the new buildings which she simply called New Cardow. The old building was sold to a then brand-new startup distillery called Glenfiddich. New Cardow had three times the capacity of the old premises and once again business boomed.

According to brewing and distilling historian Alfred Barnard

“Mrs Lewis Cumming personally conducted the business for nearly seventeen years, and to her efforts alone is the continued success of the distillery entirely due.”

She had just begun to show her son John the trade when the market suddenly took a dive. It was only a short crisis however and only two years later the distillery entered a decade-long boom again and by 1892 they had outgrown their capacity again.

Elizabeth, now an old woman, realized that the business had become bigger than their family could handle. Just one year later she sold the distillery at just the right time to John Walker & Sons, a blending house that had been a customer for years. She made a lucrative deal too and made sure that none of her workers would lose their jobs. Furthermore she negotiated that electricity was brought to their area – as one of the first places in the Spey Valley. But she didn’t let go entirely, although she herself retired: she only sold under the condition that her son was made board member and would continue to be involved in the business. And she bought 100 shares of the new company, thus securing her family’s fortune.

One year later Elizabeth died, leaving her family with a tremendous legacy and the business she helped to build still flourishing. Until this day every bottle of Cardhu Whisky has a woman on its red label, waving a flag.

Find out more about Cardhu Distillery on their website!

image credits:

1: The first Cardow farm – Link

2: Cardhu Distillery in 1893, ctsy Cardhu – Link

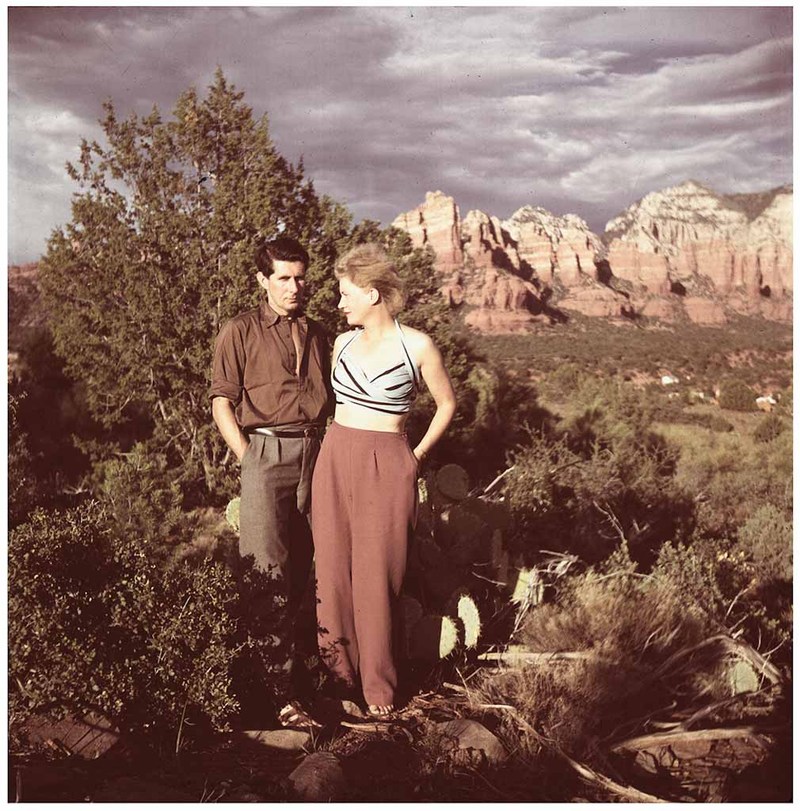

3: Cardhu Distillery, 1846 – Link

4: Elizabeth Cumming – Malt Whisky Trail on Flickr – Link

5: Cardhu Distillery, 1892 – Link

6: Elizabeth Cumming – Malt Whisky Trail on Flickr – Link

7: Cardhu 12 Jahre 40%vol. 0,7l on Home of Malts