Gabriela Mistral – The Unlikely Poet Who Won a Nobel Prize

Thinking of poetry in Chile, the first that comes to mind is Pablo Neruda. But there was another important poet before him – and she was a woman. Enter Gabriela Mistral, who overcame many, many obstacles to become a famous writer, eventually earning the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Latin American to ever do so.

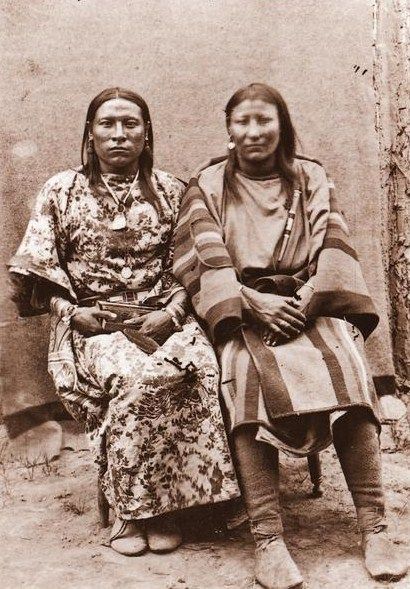

But before she became Gabriela Mistral, she was Lucila Godoy Alcayaga, a girl of Basque and Indigenous heritage born on April 7, 1889 in the city of Vicuña in northern Chile. Before Lucila turned three, her father, a teacher with the heart of a traveling poet, left the family for good and his abandoned wife moved herself and her two daughters to the Andean village of Montegrande. You can see the family’s home below.

There she found work as a seamstress and the older sister, Emelina Molina, was employed as a teacher’s aide in the same school that Lucila soon attended. But despite their hard work, their life remained a humble one. As their money was running out, Lucila had to be taken out of school when she was only twelve, but she did not give up learning and with her sister by her side, she was able to feed her thirst for knowledge. By the time she was 15 she even got a position as a teacher’s aide in the seaside town of Compañia Baja and soon she taught in the near La Serena school as well. Around the same time she published her first poems in the local newspaper, using different pseudonyms such as Alguien, Soledad and Alma.

In 1906, when she was 17, she met her first love, a railway worker named Romelio Ureta. Only three years later the young love ended abruptly, as Romelio took his own life. This had a huge impact on her life, turning her to poetry even more and melancholy and the feeling of loss should become recurring themes in her work. It was then that Gabriela Mistral was born – a name chosen in remembrance of the archangel Gabriel and the warm Mistral wind of the Mediterranean. Or maybe it was a combination of the names of two of her favourite poets, Gabriele d’Annunzio and Frédéric Mistral.

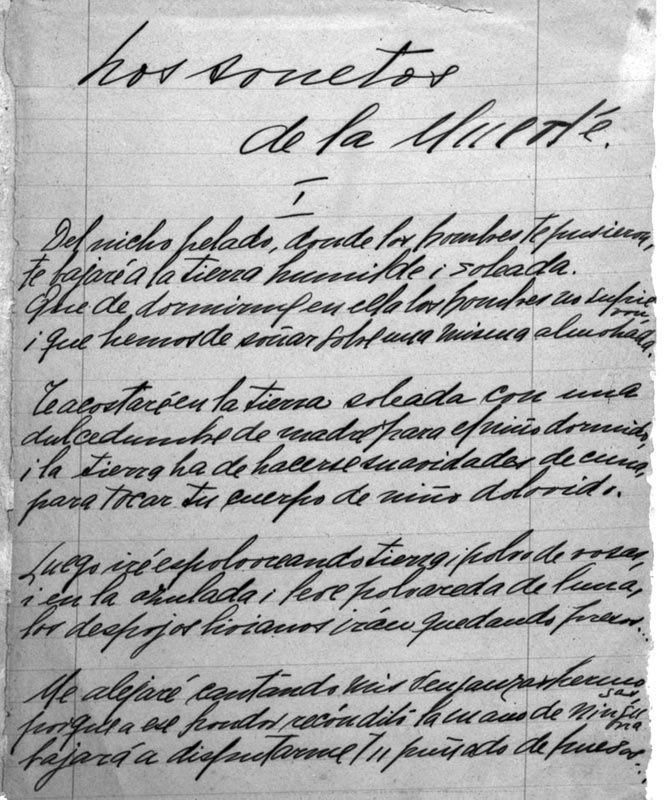

She was determined to pursue a higher education, but was turned down from attending the Normal School without explanation. Later she found out that it was her writing that had blocked that path, Gabriela’s advocacy for universal access to education did not agree with the conservative views of the school’s chaplain. Undeterred, she decided to become an educator instead. Her task was made easier by the significant lack of teachers in the country. With the help of her sister’s contacts she got hired quickly and climbed the ladder utilizing her reputation as a published author and being willing to move wherever she was needed. By 1911 she was teaching several schools at primary level and worked as an inspector as well, often in remote areas. One year later she was hired to teach at a high school in Los Andes, near the capital of Santiago, where she would stay for six years. It was there that she wrote her “Sonetos de la Muerte,” her Sonnets of Death, in memory of her lost love, processing her grief. These Sonnets were what brought Gabriela to the attention of the wider masses when they won her the prestigious National Flower Award in 1914, aged 25.

When her stay in Los Andes ended, she moved on to a high school in Punta Arenas and then to Temuco in 1920, where she met and taught the young Pablo Neruda. The next year she was elected the director of Santiago’s newest and most prestigious girls’ school, so she moved back to the capital. Not everyone agreed with her nomination though and to escape the controversy, she accepted a job offer in Mexico only one year later to work with the Mexican Minister of Education to reform the national education system.

All the while she had been publishing her work and had acquired a considerable reputation as a journalist and public speaker. In 1922 she brought out her first book, “Desolación.” And she didn’t just publish it anywhere, she did so in New York! She was just getting started though. The next year she finished another text, “Lecturas para Mujeres,” Lectures for Women, celebrating Latin American culture. Her second book came out the year after; it was a children’s book of stories and lullabies, called “Ternura,” Tenderness. This one was published in Madrid, Spain! For she had left Mexico for Washington and then New York to tour Europe.

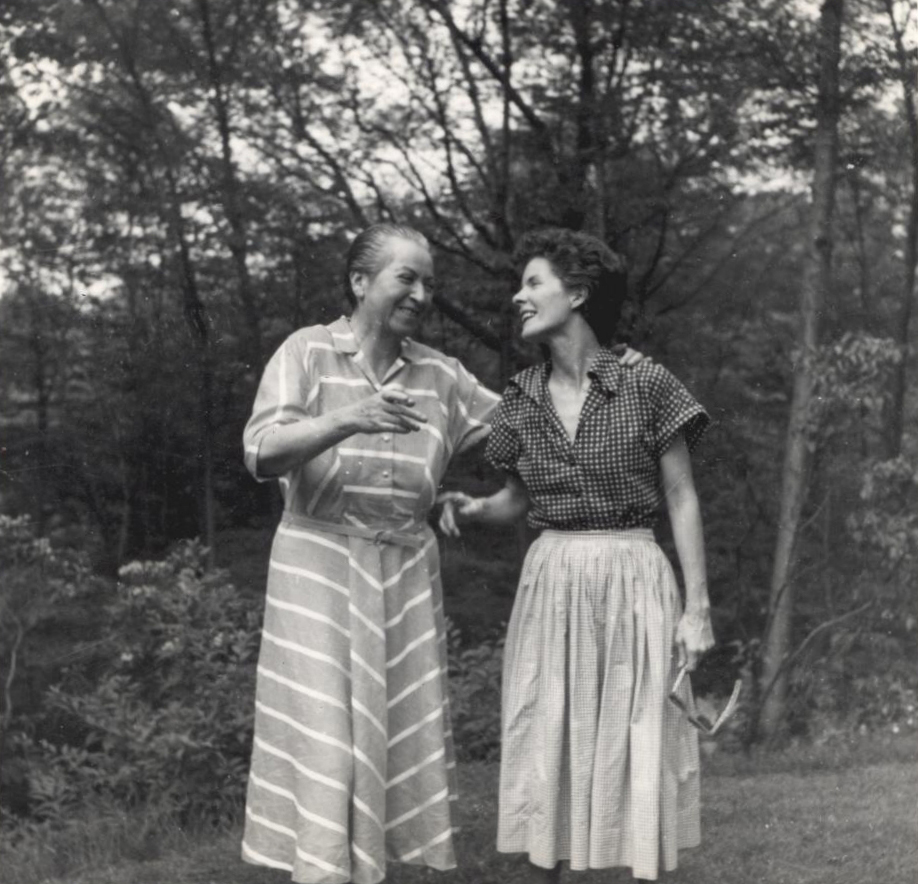

While she was a brilliant writer, she was not very good at taking care of herself; housework wasn’t really her thing and neither were finances, she didn’t like to cook and above all, she couldn’t stand being alone. Interestingly she still never married but preferred to live with women, all of them highly intelligent as herself and accomplished in their fields. One of them was Palma Guillén, a Mexican diplomat and educator, whom she met in 1922 during her time in Mexico. The two women should stay together for more than 15 years.

After a year of travelling she returned home to Chile in 1925 and retired from her teacher’s life at 36 years old. And not a moment too soon, for a law had just been passed that required teachers to have finished training at university. She had however been awarded the title of Spanish Professor by the University of Chile two years prior, although she had not had any form of formal education past the age of twelve. This shows what a remarkably intelligent woman she was and how determined to fill her head with all the knowledge she was denied by the system. This secured her a pension for life.

When she was invited to represent Latin America in the newly formed Institute for Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations, she moved to Marseilles, France with Palma and the couple adopted adopted the infant son of Gabriela’s half brother after his mother had died. Little Juan Miguel was physically disabled, which is why his father could not take care of him, but Gabriela did not care, she loved the boy as if he was her own. She supported their small family first with her journalism and then by giving lectures at universities in the US as well as Latin America. She also took up consular work, mainly in Italy and France but also in Spain, Guatemala and Brazil among others. In 1935, she was named consul for life. While working at the consulate in Madrid she once again met Pablo Neruda and was amongst the first to discover her fellow writer’s talent and originality.

All the while she kept writing and publishing her work in the Spanish-speaking world, with the help of her confidantes, the presidents of Colombia and Chile, as well as the First Lady of the US, Eleanor Roosevelt. And finally in 1938 she returned to Latin America, albeit not her home country, but Uruguay and Argentina. Her second major volume of poetry, “Tala,” was published in Buenos Aires that same year, with the proceeds going towards children orphaned by the Spanish Civil War. The book itself once more celebrated Latin American culture and heritage, but also the traditions of Mediterranean Europe – a fusion of different cultures, reflecting Gabriela’s own identity as both, European Basque and Native South American.

While they were living in Brazil, 17-year-old Juan Miguel took his own life in 1943. Gabriela was grief-stricken for she felt like she had lost a son and she blamed herself. Just one year before, her close friends, the Austrian couple Lotte and Stefan Zweig, writers who had taken residence in the city of Petrópolis like her, had chosen to end their lives as well. Furthermore her mother and sister had died not too long ago. All those wounds had not yet healed and now they were torn open once more. In 1946, Palma married a man, although she did continue to be Gabriela’s secretary and to support her emotionally. Gabriela, unable to move on, stayed in Brazil. And she remained there until two years later, when word arrived that she had won the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Latin American to ever do so, and only the fifth woman. Just as bad things seem to only come in packs in her life, so did the good. In that same year her path crossed with that of Doris Dana, a beautiful and bright young woman from New York. Doris admired the poet, who was 31 years her senior, and although Gabriela did not remember their first meeting, Doris decided to write to her. A correspondence, and eventually a friendship, ensued.

Having found herself again, she once more felt restless. And so she packed her bags and moved to San Francisco, a delegate of the United Nations and soon also a founding member of UNICEF. She then took off to Los Angeles and later took up residence in Santa Barbara, California. In 1948, Gabriela finally invited Doris to visit her, after two years of regular correspondence. Soon the friendship turned romantic and Doris, then 28, decided to stay with the poet who was 59 at the time. Soon the two women travelled together to Mexico, where Gabriela was awarded a plot of land in Veracruz to build a house on (which the couple did.)

Oh, she also snatched a doctor honoris causa from Mills College in Oakland, California in 1947 and the Chilean National Literature Prize in 1951.

Although their relationship was very happy, Doris frequently had to return to her family in New York and every time she left, Gabriela feared that she would never return. But each and every time she did. Together they left Mexico around 1950 and spent the next two years in Italy, where they met Palma again. Doris and her became fast friends and she was only too happy to have a little help in handling Gabriela’s affairs. In 1953 the poet’s health began to decline and she realized she would not be able to travel anymore; after all she was 64 years old already. She wanted to spend the rest of her life with Doris but knew that her love could never call any other place than New York her home. So they settled on a compromise.

That same year, Gabriela set out for one last triumphant visit to her home country, with Doris accompanying her of course, and she was welcomed enthusiastically. And then the couple returned to their new home. Because Gabriela hated New York City, they settled in Roslyn Harbor, not too far away. There she continued to represent Chile in the General Assembly of the United Nations and, of course, to write. One year later her final book, “Lagar,” Winepress, was published and in it were all the grief over her son, the tension of World War II and more. It was the last one to be published in her lifetime. In early 1957, Gabriela was admitted to Hempstead Hospital in New York, where she died only a few days later on January 10, aged 67. Doris had not left her side.

Below a bonus picture of the two lovebirds because they were so darn cute:

Nine days later Gabriela’s body was transferred back to her hometown of Montegrande, just as she had wished. Hundreds of thousands Chileans attended her funeral and paid their respects and the country declared three days of national mourning in her honor. At the same time her “Messages describing Chile“ were published posthumously. According to Gabriela’s testament the proceeds of her book sales in South America were to be used to help the impoverished children of Montegrande, one of which she had been too, so long ago. The proceeds from the sales in the rest of the world were supposed to go towards Doris Dana and Palma Guillén, who decided to give their parts to Chilean children in need as well. At first it looked like this wish could not be carried out as there was a law against inheriting profits yet to be made, but the decree was repealed and so her final wish came true. Doris was also the one holding all her literary legacy and she is the one who translated a selection of her poems into English and managed their publication.

Gabriela Mistral’s legacy can be found in many names all over the country. Within months of her death, a museum was opened in her birthtown of Vicuña. In 1977 an order for teaching and culture was named after her and in 1981 a private university was founded that bears her name. Once she had mentioned, jokingly I presume, that she would love the Hill of Montegrande to be named after her one day and indeed, on the day that would have been her 102nd birthday, on April 7, 1991, the street Fraile Hill was renamed Gabriela Mistral. Practically every major city in Chile has at least one street or plaza named after her. She certainly has left her mark and will not be forgotten.

image credits:

1: “House of Gabriela Mistral, Montegrande, Valle del Elqui, Coquimbo Region, Norte Chico” – © Educarchile – Link

2: “Manuscript Los Sonetos de la Muerte” – © Educarchile – Link

3: “Gabriela Mistral,” 1923 (© Archivo General Histórico del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores) – Link

4: Palma Guillén and Gabriela Mistral, undated – Link

5: “Gabriela Mistral (1889 – 1957)” – © Educarchile – Link

6: “Gabriela Mistral and Doris Dana in the garden of their house in Long Island” – © Educarchile – Link

7: “Gabriela Mistral reading on her terrace” – © Educarchile – Link

8: “Gabriela Mistral and Doris Dana on the Beach” – © Educarchile – Link