Changunak Antisarlook Andrewuk – Queen of the Reindeer

Did you know that Alaska used to be Russian territory? It was only sold to the US around 1870 and suddenly the social landscape changed. Into these tumultuous times today’s heroine was born and against all odds, she became one of the richest people in the state. Hear the story of Changunak Antisarlook Andrewuk, Sinrock Mary, the Queen of the Reindeer.

When Alaska changed government, Changunak was born. Her mother was of the Native Inupiat people and her father was Russian. Likely a merchant or fur trader, he came to Alaska to make money, but returned home once his contract with the trading company ran out – alone. Their fate was not a singular one; when the Russian traders departed, they left behind a new generation of children with mixed heritage.

Changunak’s childhood was never boring. She grew up in St. Michael, a trading post where lots and lots of foreign ships docked and where there was always something to see. She observed the strangest people coming from these ships, dressed in foreign clothing and speaking languages she had never heard before. The girl soaked up everything she saw and before she was past her teens she spoke Russian and English besides her native tongue, Inupiat, and several of its dialects. But not only did she learn about other cultures but also her own. Her mother taught her the ancient ways of her people. She learned about herbalism, how to hunt and set traps and how to tan and sew animal hide, the trades of her ancestors. But most importantly she learned generosity, as was the Inupiat way.

During their travels the Captain once more witnessed the Native Alaskan’s fight against the long, harsh winters, against starvation, and an idea that had been brewing in his head for years finally took form. The Chukchi people of Siberia were herding reindeers, why couldn’t the Alaskans? They just needed to ship the deer over, because at that point there were none in North America. Of course such a plan needed time but in 1892, only two years after he had delivered them back home, the Captain stood at the door of the Antisarlook family once again. This time he asked them to come with him to Siberia to help with the negotiations. And once again they sailed out on the Bear.

Arriving at their destination, they met up with a delegation of Chukchi and soon enough Changunak was called up to translate, being the only one in the party to speak Russian. She could however not fully understand the Siberian dialect, which angered one of the men who struck her right across the face. She did not flinch but instead stood tall, calmy asking in Russian: “Is there anyone who can understand what I’m saying?” Slowly one of the Chukchi raised his hand. “Come over here and help me,” she demanded. And he came and stood next to her. He would translate his comrades’ words into Russian which she then would translate into English for the crew of the Bear. From there negotiations went smoothly and the ship returned to Alaska, having secured 1300 reindeers to arrive over the course of the next four years. The Teller Reindeer Station was opened to teach the Alaskan population how to care for the new animals and husband Charlie began an apprenticeship there. During that time Changunak noticed that contrary to their original purpose, the reindeer were exclusively distributed amongst missionary posts and she complained. Eventually the government gave in to her constant pressure and Charlie and Changunak were the first Inupiat to own their own herd of reindeer.

Her husband did return, albeit two years later around 1900, with 100 deer lost and in terrible health. He had contracted the measles and despite her care, he died quickly. Changunak did not have time to grieve long though. She had just buried her husband as word arrived that she might not keep her herd, being a woman and all. Finally she won the right to keep half of the couples 500 animals. But her troubles were far from over. In 1902 the gold rush had arrived in Alaska and miners were flooding the small settlements, taking the reindeer as easy ressources. Parts of Changunak’s herd was stolen to serve as packing animals or shot for food and their remains left to rot on the tundra. The officials were worrying that soon her entire herd would be gone and decided it would be best to take the animals from her and move them farther north to safer ground. But Changunak would have none of it. Instead she went south with her stock, resettling in the village of Unalakleet.

Safe from the miners, she was now confronted with another problem: word had gotten out that the Reindeer Queen was widowed and suitors lined up. Everyone wanted to get their hands on the biggest herd in the state and thus the woman it belonged to. She refused them all. But not only the suitors wanted their piece of the cake, Charlie’s brothers too claimed that the herd belonged to them; they referred to the ancient Inupiat ways according to which the widow only gets what the brothers give her. She reminded them that they were living under white man’s laws now and according to those the woman inherits the man’s property. The legal battle went on for seven years but eventually she won. She was now the undisputed owner of the largest reindeer herd in the entire Arctic.

Now almost 70, Changunak realized that the world around her had changed fundamentally. There were fewer and fewer reindeer now and she became too old to care for her own herd. Two of her grandchildren moved in with her to lend her a had. She became known as the village elder who had known the Russians and people would bring her hides to make into shoes, the way her ancestors had done it, the way her mother had taught her.

On a winter’s day in 1948 Changunak Antisarlook Andrewuk, Sinrock Mary was pronounced dead. She received a communal burial and is remembered dearly by her community, not only as the Reindeer Queen, but also as someone who kept the Inupiat way alive against all odds. Until this day whenever reindeer are seen in the north people think of her. And sometimes people say they can still see her large herd roaming the hills.

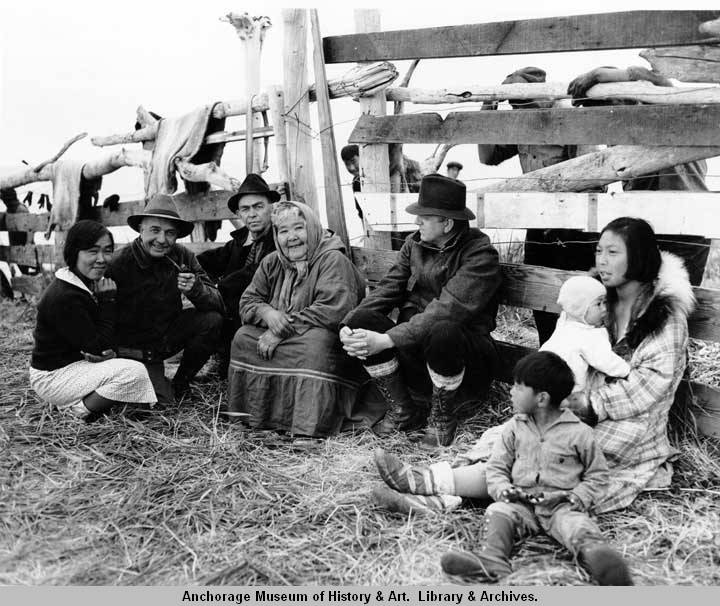

image credits:

1: “My Great-Great Grandmother Sinrock Mary (1870 -1948)” – Jodi Velez-Newell’s Eskimo Heritage Page

2: “Reindeer Committee with Esther Oliver, Sinrock Mary, Mrs. Willie Aconran [sic] with children, Clyde and Pauline, Kliktarek [sic] corral,” 1938 – © Anchorage Museum (AMRC-b75-175-161)

3: “Sinrock Mary and Esther Oliver. Klikiktarek [sic], Alaska,” 1938 – © Anchorage Museum (AMRC-b75-175-160)

4: “Sinrock Mary. Klikiktarek [sic], Alaska,” 1938 – © Anchorage Museum (AMRC-b75-175-158)