Hipparchia of Maroneia – A Cynic Life

Today’s article is taking us to the philosophers of Ancient Greece, specifically the Cynics. And to a woman who challenged the conventions of a philosophical school devoted to challenging society’s conventions. Meet one of the few female philosophers of the time, Hipparchia of Maroneia.

As her name suggests, Hipparchia was born around 350 BC in Maroneia, a small town on the coastline of the Greek region of Thrace, and her birth was soon followed by that of her brother Metrocles – with whom this story actually begins. You see, he was a philosopher’s student and quickly won over a teenage Hipparchia as well. One day Metrocles came home mortified, he had farted while giving a speech at the Lyceum, what an embarrassment! Promptly he locked himself up in his room, set on starving himself to death. Enter Crates, a Cynic philosopher who had heard of the situation and came to resolve it. Calling on the despairing young man, he convinced him that his actions had been an entirely natural act and no cause for shame. Intrigued by this philosophical approach, Metrocles became a follower of Crates and soon he introduced him to his family. To enable him to study with his new mentor, the whole family moved to Athens, the cultural hotspot of Ancient Greece.

While his parents must have been incredibly grateful that their son had refrained from suicide, they were less than happy when Hipparchia announced that she planned on marrying Crates. They pleaded with her to reconsider, to choose one of her more “fitting” suitors, after all he was already an old man at the time, but to no avail. They only succeeded in having their second child threatening suicide as well, should they not stand aside. To understand their opposition, you need to understand the life a Cynic was leading. Cynicism teaches that human life should not be limited and complicated by the conventions and traditions of society, but should be lived in accordance with nature. This meant renouncing all physical possessions, only keeping that what is necessary, and acting according to natural impulses instead of societal norms. That included the institution of marriage which was seen as impeding on the individual’s personal freedom.

Failing to talk Hipparchia out of her idea and unable to intervene further, her parents begged Crates to talk some sense into her. Let’s say, the talk didn’t exactly go as planned. He pictured their life together in the bleakest colours, home- and penniless, living on the charity of others and owning nothing but the clothes they wore. She remained certain that his kindness, empathy and intelligence was enough for her to be happy and worth more than the wealth that surrounded her at the moment. Running out of ideas, Crates supposedly tore off his cloak, hoping to scare her off with his age and probably unkempt appearance, announcing “this is the groom, and these are his possessions; choose accordingly.” And Hipparchia chose him. They were married around 326 BC.

It was a happy marriage and Hipparchia turned out to be right. She did not miss her former life in luxury and the marriage went on to last more than 30 years until his death around 285 BC. She lived out the last five-ish years of her life as a content woman. But back to her younger years. Besides her philosophical lectures she also worked as a counsellor for those in need, never charging but gladly accepting donations. One of her specialities was marriage counselling, obviously. It is also reported that the couple had at least one son, named Pasicles, and one daughter. They were raised according to their parents’ values, sleeping in a tortoise shell cradle and when her daughter wanted to get married, her parents did not object. They did however ask that she lived with her intended for one month before making a final decision. This marks the first trial marriage in history – it is not known if it worked out or not.

Hipparchia quickly became popular with other Cynics, so much that they would later make an exception for her whenever they talked about their opposition to marriage. They figured that she truly lived according to Cynic values, challenging their own traditions by marrying in the first place and those of society by renouncing all possessions and becoming a philosopher in doing so. However not everyone was impressed.

Hipparchia had a habit of attending philosophical discussions and dinner parties with her husband, something respectable women usually refrained from. At one such banquet she was approached by a man named Theodorus who questioned her right to be there. She retorted that it could not be wrong if he was doing it, so it could not be wrong for her and swiftly added that, in conclusion, if it isn’t wrong for him to hit himself, it would not be wrong for her to hit him as well. Hurt, but not defeated, he tried another jab by asking if she wasn’t neglecting her work at the loom in order to attend a banquet. She answered that, yes, she was, but wasn’t it right to devote herself to education and knowledge instead of such useless tasks? Theodorus had no comeback. An anecdote recalls that at loss for a better argument, he stripped her of her cloak, but Hipparchia did not flinch. To her nudity was natural and not a reason for shame.

She had used her understanding of Cynic philosophy to free herself.

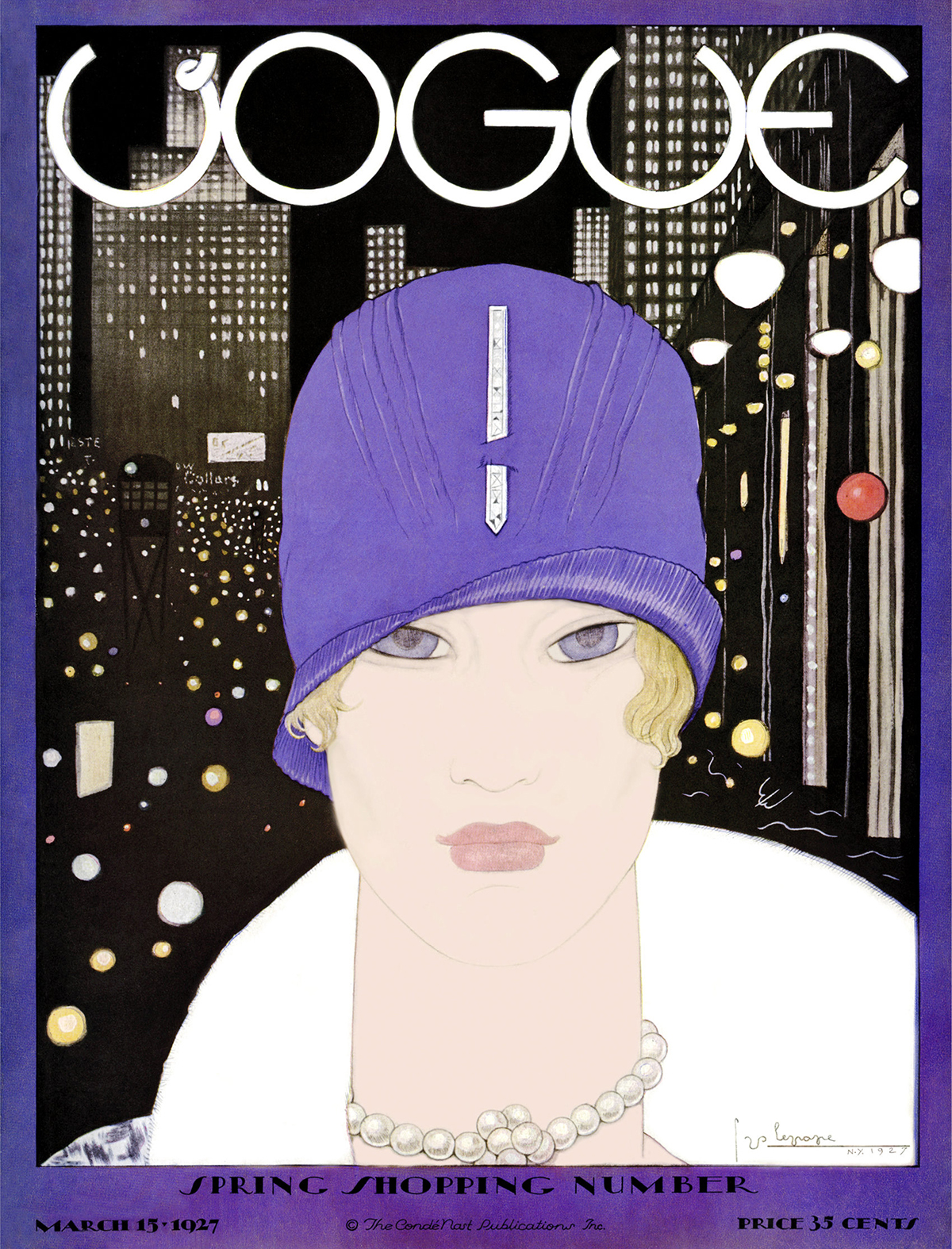

image credits:

1: Engraving depicting the Greek philosophers Hipparchia of Maroneia and Crates of Thebes. From the book Proefsteen van de Trou-ringh (Touchstone of the Wedding Ring) written by Jacob Cats. Hipparchia and Crates are depicted wearing 17th-century clothing. In the scene depicted, Crates is trying to dissuade Hipparchia from her affections for him by pointing to his head to show how ugly he is. (1637) – Uploaded to Wikimedia Commons – Link

2: Wall painting showing the Cynic philosophers Crates and Hipparchia. From the garden of the Villa Farnesina, Museo delle Terme, Rome (ca. 1st century) – Uploaded to Wikimedia Commons – Link