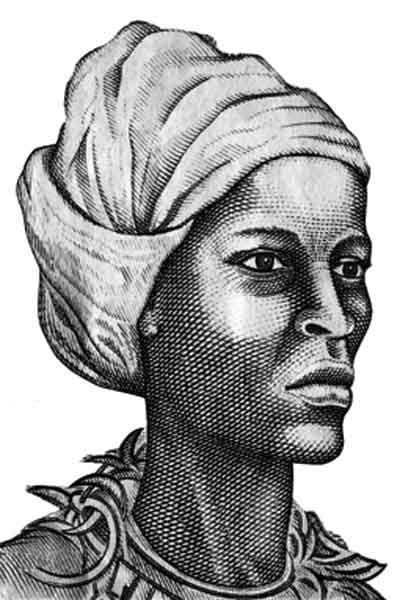

Queen Nanny – Leader of the Maroons

This is the story of a woman who led the Jamaican Maroons in their fight against slavery and who had the British tremble in fear. This is the story of Queen Nanny.

There are few written accounts of her life and the ones existing were written by the British and thus are less than favourable. Fortunately stories have been passed down for generations, so her story is not lost to us. It is not always easy to separate fact from fiction, but I will try.

Nanny had not always lived in Jamaica. She was born around 1686 in Ghana, which was called the Gold Coast back then, presumably a child of the Ashanti tribe. At some point, her village must have been captured as she was sold and shipped to Jamaica alongside quite a few members of her family. Arriving on the island far from home, she was sold to a sugar plantation in Saint Thomas, near Port Royal. There are some accounts that state she was of African nobility emigrated willingly as a free woman and even married, although none of her children survived. In regards to her further life however, I find the story of her enslavement more likely, so I’m going to follow that narrative.

Life on the plantation was hard, they were treated harshly by their owners, but there were stories of other slaves who had managed to run away and a spark of hope lit up. It didn’t take long until Nanny and three other men who are often called her brothers, planned their escape – and succeeded. This happened around 1690. They made their way into the jungle of the Blue Mountains where they would be harder to find and eventually resolved to split up, so they could rally other maroons and organize the resistance. Nanny decided to remain in the Blue Mountains, where she would become the leader of the Windward Maroons of the East, while two of her brothers would head the Leeward Maroons in the West.

Word got out amongst the slaves that there was refuge in the mountains and her camp grew. By 1720 the area she controlled had become a small city which they named Nanny Town. The settlement was built strategically, overlooking the surrounding landscape while remaining hidden itself. It was only accessible via a small path that could only be walked by one person. When the British attacked, Nanny’s men were able to kill them one by one, so even a relatively small band of Maroons were able to eliminate a much larger and better equipped force. Even though the British did manage to capture the stronghold on several occasions, they never managed to hold it. Nanny and her people knew the surroundings perfectly and had adjusted their fighting style accordingly. Their precise guerilla attacks drove their adversaries home quickly. But they did not only defend, they also attacked. They raided plantations to free more slaves and thus add to their numbers, as well as to collect supplies and acquire new weaponry. Thanks to their efforts, about 1000 slaves were freed – by the Windward Maroons alone.

Nanny was a brilliant strategist and employed several decoys to ensure the safety of her people. She would have the British led into traps an ambushes and even when they retaliated, the dead amongst the Maroons were few, less than ten people. Queen Nanny was also an obeah woman, a spiritual healer, a status that earned her even more respect besides the obvious plus side of being able to care for her wounded warriors. She also encouraged her people to continue to honor their traditions and kept them alive herself by passing down the legends, songs and customs of her people. This could also be seen as a tactical maneuver, as this practice instilled a big sense of community and pride in the Windward Maroons.

These skirmishes went on for more than a decade until in 1739 the Maroon War was over. The Leeward Maroons had already agreed to a peace treaty that granted them a plot of land but had them promise not to free any more slaves and to assist in catching any new runaways. That last clause didn’t sit quite right with Nanny and she didn’t sign, preferring war over treason. Eventually however, succumbing to pressure from her brothers who had already signed, she agreed and accepted the land she and her people were granted.

So Nanny Town was abandoned and New Nanny Town was founded. Now they mainly focused on the cultivation of crops and livestock as well as hunting. They did produce their own food before as well, but now there were no attacks or raids getting in the way of a peaceful life. The community itself was organized much like the Ashanti communities of Ghana, with an economy based on trading produce for other necessities. Queen Nanny had made herself a new home away from home and she continued to live in this place until she passed away around 1755 as an old woman. Another story tells that she was killed around 1733 in one of the many battles with the British, although I find that unlikely, as the plot of land was allocated to “Nanny and the people now residing with her and their heirs” which indicates that she was still alive in 1740.

While the original Nanny Town has since disappeared, New Nanny Town still exists, although it is now named Moore Town. Until this day many women there are being called by the honorific “Nanny” although there is only one Queen. In 1976 she was made a National Hero of Jamaica – the only woman amongst them – and her portrait can be found on the Jamaican 500 Dollar Bill, which is also commonly known as a “Nanny.” On top of that numerous streets and places are named after her and a statue has been erected in Moore Town. Still she continues to inspire Jamaicans to create art and there even is a movie about her life!

While often ignored by Western scholars, she remains alive in the hearts of her people, a symbol of their strength and unity.