Amanirenas – One-Eyed Warrior Queen

This time I’m telling you about the time the Roman Empire set its mind to conquering the Kingdom of Kush where it was met by a fierce one-eyed warrior queen who would continue to fight back for seven years and eventually pushed Rome out of her country. This is the story of Amanirenas and you’re in for a ride.

We’re jumping right into the story as not much is known about Amanirenas’ early years, other than that she was born around 60 B.C. The story is set in the Nubian kingdom of Kush, a relatively small but quite powerful kingdom in what is now Sudan. Amanirenas became Kandake, Queen, of Kush after her husband died in battle around 40 B.C. In inscriptions about her she is titled Qore and Kandake, King and Queen, clearly showing her as the kingdom’s sole ruler. But enough with the foreword, let’s get into the warring bit, shall we?!

Amanirenas ruled her kingdom diligently and apparently without any major problems, but after ten years the Roman Empire took Egypt, their direct neighbor in the north. That alone would have been a blessing for Kush who would have lost their main competitor, but Rome turned its eyes south. Kush was a small kingdom and should the Romans truly wage war on them, their chances weren’t looking too good. However there was a bit of trouble on another front, namely Arabia, so they didn’t attack immediately. It’s not certain whether Amanirenas knew of Rome’s expansion plans, but since that was basically their whole deal, she probably anticipated it. So she struck first.

The first battles began in 27 B.C. but the big invasion came three years later. In 24 B.C. an army of 30.000 marched against Roman Egypt, Amanirenas and her son at the helm. Even though it seems to have been one of the battles that followed in which the Kandake lost her eye, the Kushites were ultimately successful.

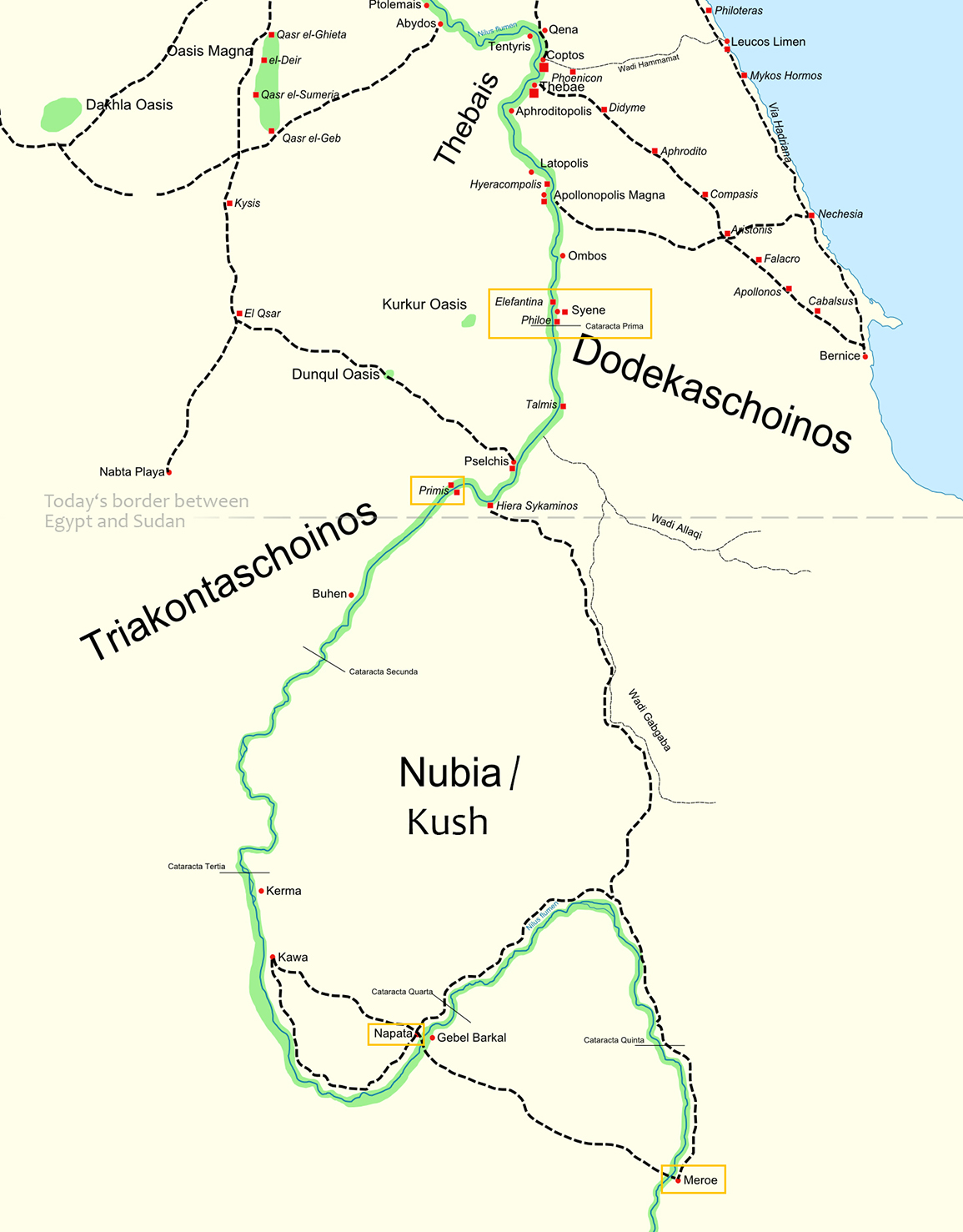

They captured the cities of Syene and Philae as well as Elephantine Island, decapitating all the statues of Augustus Caesar they came across. Triumphant the Kushites returned home, with a rich bounty and war prisoners in tow – and at least one of Augustus’ bronze heads. However victory didn’t last long and in the same year the Romans pushed back, retaking their cities and advancing into Nubian territory. They took Kush’s old capital Napata and although they retreated north again relatively quickly it was a debilitating defeat.

Many Kushites were sold into slavery and the newly established Roman garrison at Primis proved undefeatable. But Amanirenas would not give in.

For three more years she waged war on the Romans. There are stories of war elephants as well as about the Kandake feeding war prisoners to her pet lion. The former are likely to be true, although Kush probably did not use elephants as much as Carthage did, while the latter might be an exaggeration but who is to say for certain.

Even though Amanirenas didn’t succeed in reconquering her land, the Romans had to give up eventually. Yes, Kush was small and its military strength inferior to that of their opponents, but it was also too far off to easily call on reinforcements and the goods needed to sustain an army. Add the harsh environment and significant armed resistance led by our heroine and it was just too much to handle.

Around 20 B.C. a peace treaty was forged that strongly favoured Kush. Rome was to retreat from their post at Primis and the surrounding lands (called Triakontaschoinos, the Thirty-Mile-Strip) and there was no tribute to be paid whatsoever. The Romans got to keep a smaller strip of land (the Dodekashoinos or ‘Twelve-Mile Lands’) to establish a military border zone, but apparently there were no subsequent attacks. In fact this peace treaty was honored until way after Amanirenas’ death around 10 B.C. and the Kushite Kingdom thrived for more than 300 years.

You might wonder why all we know about her is related to her military exploits. Well, most of the sources on her that exist are Roman. But even they had to admit she was brave and strong. While Kush did leave a fair share of inscriptions, they had their own system of hieroglyphs that no one has been able to really decipher to this day. They did leave us one obvious message though. Remember the decapitated statues? So, in 1912 a temple that had apparently been dedicated to victory was unearthed in Meroë, the new capital of Kush. In this temple, the archeologists found the bronze head of Augustus Caesar. It was found buried underneath the steps.

image credits:

1: Map – User Gigillo83 in Wikimedia Commons, 2010 – modified: highlighted the places important to the story, added the modern border of Sudan and Egypt, added “Kush” to Nubia as called in the article – Link

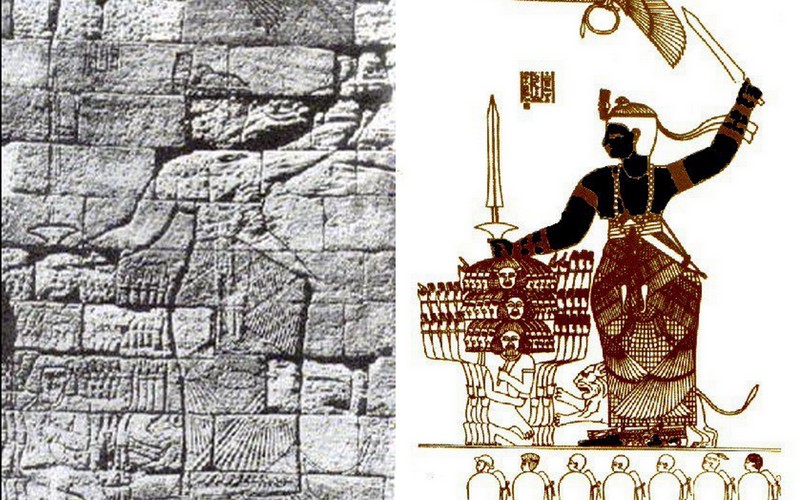

2: Kandake Amanirenas as identified by JC Coovi Gomez on the Barwa’s Beg pyramid No. 6 (*Barwa was another name of Kush at that time. The Pyramids mentioned are located at Meroë.) – Link

3: The Pyramids at the foot of Jebel Barkal, Karima, Sudan (*where Amanirenas was likely buried) by Maurice Chédel, 1884 – Link