Jeanne Hachette – Defender of Beauvais

The story I’m telling you today is a relatively short one, but exciting nonetheless! While Jeanne was definitely a real person, the accounts on her life differ from source to source, but one thing is clear, she was a total badass. When her city was attacked, many of the women living there refused to be bystanders and joined the fight – including 18 year old Jeanne, who grabbed a hatchet and played a key role in defending the city from capture. But let’s start at the beginning.

Born around 1454 in the city of Beauvais, her real last name was either Fourquet or Laisné. She might have been the daughter of a butcher and, after her father’s death, could have been adopted by one of the city guards, which would explain the different names. Whatever the case, she was apparently not unfamiliar with blades. Another story tells that since childhood, she adored her namesake Jeanne d’Arc and dreamt of being like her someday. And she got her chance.

Fast forward to 1472 when the Duke of Burgundy, who was revolting against the King – long story and not all that important for this article – advanced on Beauvais with an army of 80.000. They had already laid waste to the surrounding villages in an especially brutal fashion, hoping to scare the city into surrender. On June 27, workers on the cathedral roof spotted the approaching army and raised the alarm. The first onslaught was overwhelming. While Beauvais was well fortified, it had no artillery and the Burgundian soldiers were climbing the wall. Swiftly one of the suburbs was taken and there was a huge hole in one of the city gates. But the city didn’t surrender. Instead the citizens took up arms and threw themselves into battle – and not only the men, but women and children as well. Hot water, oil and molten lead were poured on the enemy soldiers storming the gate, men and women were blocking the gate, armed with whatever was available, sometimes only with their fists. But slowly they were losing ground and slowly their courage wavered.

Amidst all this chaos, 18-year-old Jeanne grabbed a hatchet and climbed the city walls with a band of women, all armed for combat. The Burgundians were still scaling the walls and the women got to work, shoving enemies back down and toppling ladders. Some soldiers got through though and one of them was intent on planting the Burgundian flag on top of the wall, a sign of victory. Jeanne swiftly threw him into the moat, holding the flag high over her head. This reignited the bravery of her fellow fighters and the battle waged on. At some point the broken gate was set on fire and kept aflame to make it harder for the enemies to enter.

For two weeks they kept the flames burning until the Duke decided to attack another portion of town. Cannonballs destroyed big parts of the city, but he couldn’t get through the walls to conquer it. Even though Beauvais didn’t have any artillery, the defenders – many of them women – were valiant and quite inventive, hurling stones, torches and boiling water at the enemy. Wherever the soldiers attacked, a defense system was already in place, keeping them at bay.

On July 22nd, after almost a month of fighting, the Duke had to retreat. He lost around 3.000 men, including about 20 lords against a city that had no ranged weaponry and an army that mainly consisted of citizens, many of them women – a humiliating defeat.

A defeat that might just have turned the tides of the Duke’s revolt. You see, he might have been able to beat the King… had he not wasted that much time on the city of Beauvais. As things were, he was forced to retreat to his own lands. The revolt had failed. King Louis XI recognized the contribution of the valiant citizens of Beauvais and granted the town certain privileges, like a lower tax rate. He also recognized the important role women had played in this defense and suspended the sumptuary laws which were common at the time. That means women were allowed to wear whatever clothing they liked, regardless of rank or gender norms.

And Jeanne? Jeanne was rewarded as well. Not only did she get money, but she and her descendants would never have to pay taxes, ever. Furthermore she was allowed to marry the man she loved, Collin Pillon, and some even say it was the King himself who held the ceremony.

That year the first Fêtes de l’Assaut (“Celebration of the Assault” – weird name, I know) is held with a procession through the city with Jeanne at the front, carrying the flag she conquered. Behind her the women of the city, honored for their inventiveness in ammunition. Since then this procession is held every year on the last weekend of June and it’s often called Fêtes Jeanne Hachette after our heroine and the name she became known for.

From then on her traces are lost in time. But her memory lives on forever in the town of Beauvais – their very own Jeanne d’Arc.

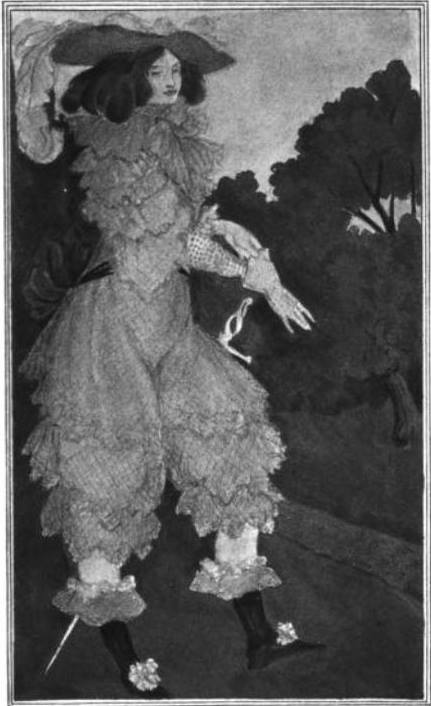

image credits:

1: Jeanne Hachette Transformation cards (c. 1870, image cropped) – Steffen Völkel Rare Books – Link

2: “Beauvais (Oise, France) – Statue de Jeanne Hachette” (2008) by User Markus3 (Marc Roussel) in Wikimedia Commons – Link

3: “The women of Beauvais defending their city under Jeanne Hachette” from page 172 of “The story of the greatest nations, from the dawn of history to the twentieth century” by E.S. Ellis & C.F. Horne, 1900 – page scan uploaded to flickr by Internet Archive Book Images – Link

4: “La statue de Jeanne Hachette” by Béatrice Butstraen on her blog Les petits plats de Béa [French], 2018 – Link