In World War I a nurse was executed for treason by a firing squad. Do you wonder how she ended up like that?

Please read on.

Edith Cavell’s life didn’t start out that extraordinarily. She was born in Norwich in 1865 as the eldest of four children. Although the family wasn’t exactly rich, her parents believed into sharing what they had with the less fortunate. A sentiment that stayed with Edith all her life. She was educated in several boarding schools, like quite a few girls with her upbringing, and after graduating started working as a governess. After a brief period of travelling however, her father fell sick and she decided to return home and care for him. This was when the seed of her wish to become a nurse was planted.

Eventually he recovered and Edith began her job as a nurse probationer in London Hospital when she was 30. It was a hard job, but it showed she had a real talent for it. She even earned a medal for her work during a typhoid outbreak in Kent! Edith was dedicated to her job, working in several hospitals and visiting patients in their homes.

In 1907, she was approached by Dr Antoine Depage, the director of a newly established nursing school in Brussels, who wanted her to teach there. Upon realizing how poorly trained Belgian nurses were (as it has been long regarded a male profession there) she accepted and packed her bags. Her teaching was strict and her standards high, but the hard work paid off. Even Queen Elizabeth asked for a nurse trained there when she broke her arm, giving the faculty the royal seal of approval. In 1910, Edith decided it was time for a professional nursing journal and promptly launched one herself, called L’infirmière. And so her reputation grew and within a year she trained nurses in 3 hospitals, 24 schools, and 13 kindergartens in Belgium. On the right, that’s her when she lived in Brussels. The dog on the right, “Jack” was rescued after her death.

Taking a break from her busy life, she was just visiting her mother (her father had died shortly before) when World War I broke out. Hastily Edith returned to Brussels to care for all the wounded soldiers that came flooding in. For her efforts she became matron of the hospital, overseeing the nurses’ activities and organizing them. In the picture you can see her amidst her nurse squad.

When the Germans occupied Belgium in 1914, Edith began sheltering soldiers – both, Allied and German – and helped them flee the country. Not only did she hide them in her own cellar until trusted guides were found to send them to the next station in the smuggling network, she also invented ruses for them to be able to flee safely. And that’s not all! Written on fabric and sewn into clothes and hidden in shoes, Edith and her organization sent military intel to the British. Unfortunately Edith was a generally outspoken person, so she wasn’t exactly inconspicuous. And in 1915 she was betrayed by a member of her network (who ironically was executed all the same) and arrested by the German military police.

For 10 weeks she was kept in solitary confinement but refused to talk. Eventually though, she was tricked. Her captors told her that her comrades had already confessed and if she did too, she could save them from execution. Naively she believed them. Edith signed her confession one day before her trial. Unfortunately she was a little too thorough, admitting not only to helping Allied soldiers flee the country but also sending them to a country at war with Germany – namely Britain, from where they would often send her postcards upon their safe arrival. Never leave a paper trail, people! Unfortunately the punishment for that crime was death, according to German military law (which, in times of war, did not only apply to Germans but to all people in occupied areas.) So she was sentenced to death by shooting.

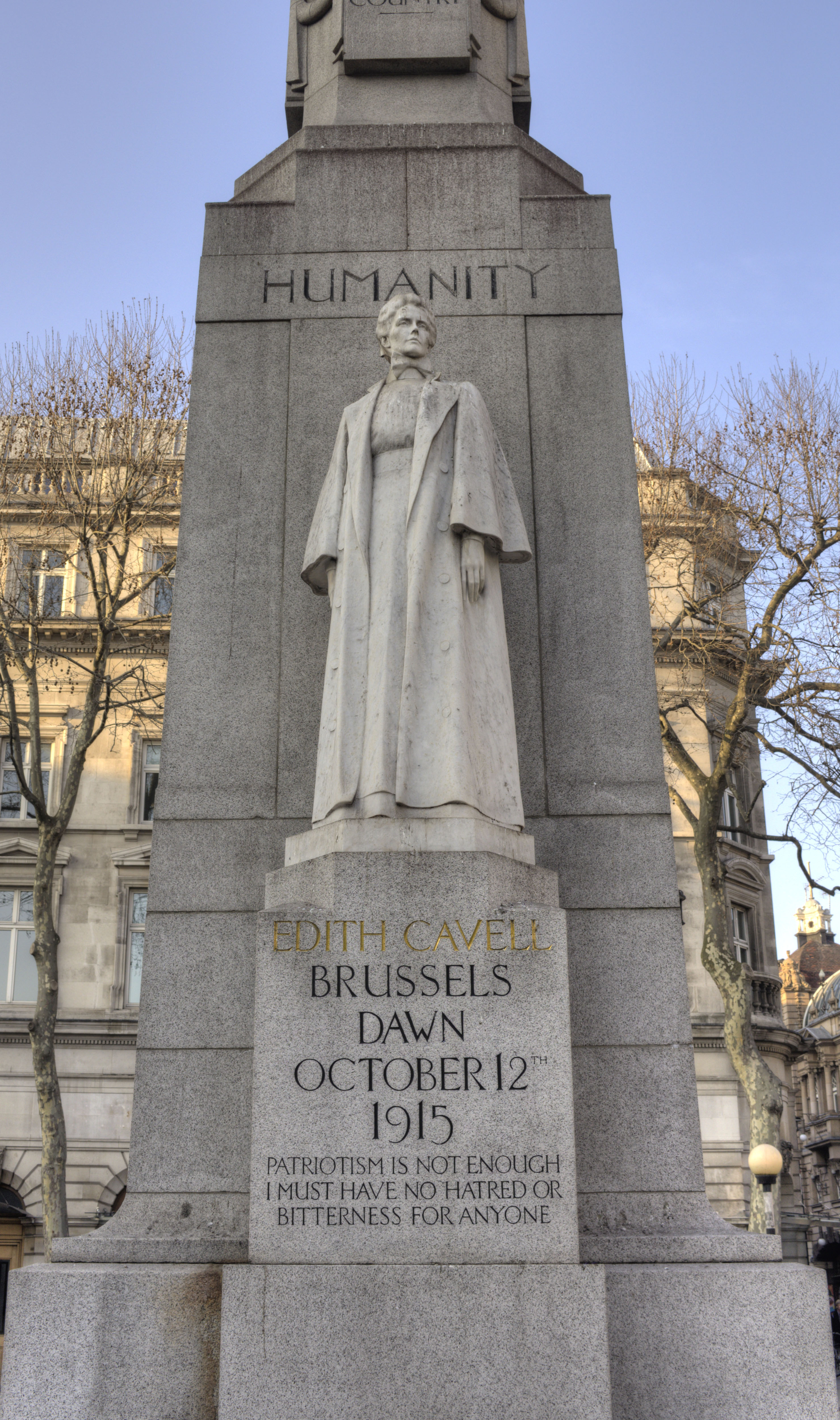

Interestingly enough, quite a few countries had something to say about this. Not only did Great Britain try to save her (denying the espionage charge of course), but the formerly neutral countries of Spain and the USA objected to the sentence as well. Unfortunately they were powerless. And so on 12th October 1915, Edith Cavell was executed by a German firing squad. On the night before her execution, she said to the priest who gave her Holy Communion: “Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.” These words were inscribed to the statue of her that still stands in St. Martin’s Place, near Trafalgar Square in London (see the picture). Her final words are recorded to have been: “Tell my loved ones later on that my soul, as I believe, is safe, and that I am glad to die for my country.”

As the mention of a statue in her honor might have indicated, killing Edith was a propaganda catastrophe for Germany. Even though Edith herself said, she had expected the trial’s outcome and believed it to be just (after all she had committed the offense she was charged for), she was hailed a martyr. In Great Britain her death was told over and over by newspapers, pamphlets and books (often not very accurately and always dropping her espionage activities) which instilled strong anti-German sentiments in the population. All because she was a woman and a nurse – the picture of innocence. Especially her fearless approach to death contributed to her popularity.

One more quote of hers: “I have no fear or shrinking; I have seen death so often it is not strange, or fearful to me!”

further reading: https://edithcavell.org.uk/

image credits:

Edith and her dogs: Imperial War Museum © IWM (Q 32930)

Nurse Squad: Imperial War Museum © IWM (Q 70204)

Statue: User Prioryman in Wikimedia Commons – Link

0 Comments