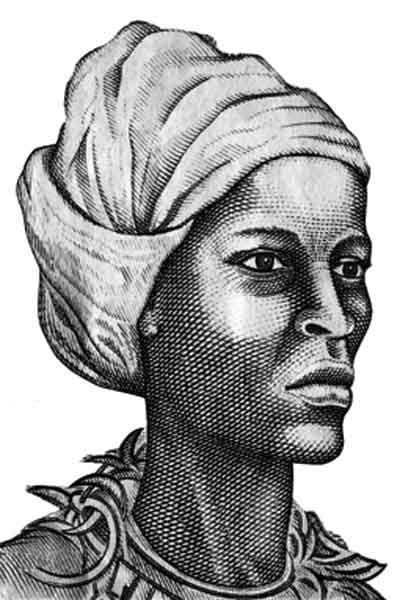

Njinga Mbande – The Mother of Angola

It is Black History Month and I am back! This time with a heroine who ruled her country for 40 years and was incredibly successful in defending it from colonization. Her strategic knowledge, cultural wisdom, thorough education and negotiation skills make her an outstanding example of female rulership. I present to you Queen Njinga Mbande of Ndongo and Matamba.

This story begins a little before our heroine’s birth when in 1560 the Portuguese arrived on the shores of Ndongo, a country that is now called Angola. They were welcomed by the King of Ndongo, Njinga’s grandfather, who was suspicious but allowed them to stay …under close surveillance and being forbidden to leave unauthorized. The next five years the Portuguese worked on a beneficial image, teaching the population how to read and write, all the while observing the culture and estimating the country’s wealth. Finally the King made a deal with Paulo Dias de Novais, the leader of the Portuguese exploration, to enlist help in defending his land against the neighboring kingdoms. He allowed them to leave Ndongo to return with an army to help. Bad plan. In 1575 the Portuguese did indeed return with an army, however not to aid Ndongo but instead to seize it in the name of the crown. The people were caught completely off-guard, and despite fighting bravely, they couldn’t compete with the firepower of the invaders. And so the people of Ndongo were forced to retreat.

Fast forward six to eight years to the birth of our heroine. By now the Portuguese colonizers had claimed the coast of Ndongo, established the city of Luanda and renamed the country Angola. After they discovered there to be no valuable minerals, they made it their mission to make Luanda the biggest slave-trading post in all of Africa. It was in these tumultuous times that Njinga and her siblings, two sisters and a brother, grew up. When she was around ten, her grandfather died and her father became King. Njinga was his favourite and she was allowed to sit in on war meetings and other stately affairs, trained in battle and learned to read and write in Portuguese from the missionaries. Often she fought alongside her father and brother not only against the colonizers but also neighboring kingdoms. And so they lived for the next 25 years, fighting for what was left of their home and defending it the best they could.

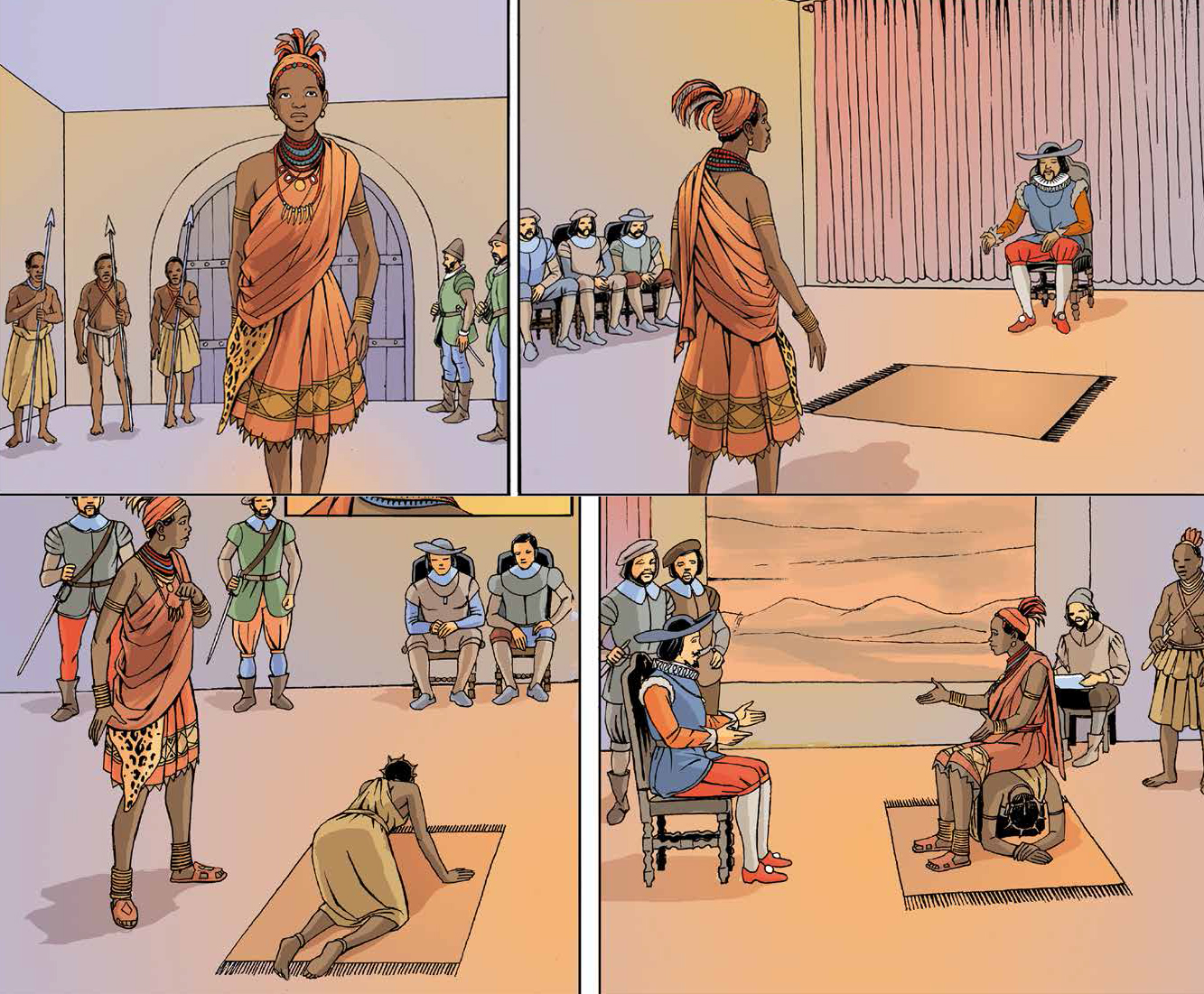

When Njinga was around 35, in 1617, her father died and her brother Ngola Mbande succeeded him on the throne. However he neither had his father’s charisma nor his sister’s intelligence and he feared her. To make sure she would not plot against him, he had her infant son slain and her sterilized. Afraid for her life, Njinga fled to the neighboring kingdom of Matamba. With his sister gone, Ngola declared war on the Portuguese but suffered defeat after defeat. Finally five years later he gave in to his elders’ advice to send Njinga to negotiate a peace treaty. The land was ravaged by famine and the slave trade didn’t look so peachy either, so the colonizers were quite interested in peace as well. Njinga was the best choice for a negotiator, speaking fluent Portuguese and being well-versed in stately affairs. And so she set out to Luanda to speak for her people. Travelling through the country she met people who had lost their homes and families and slaves who had managed to escape. She sent them all to Ndongo, promising them safety.

Finally Njinga arrived at Luanda and for the first time she saw her ancestral land. It had been completely transformed, had become a crowded city. Not only black and white people lived there, but also their children of mixed race – something Njinga had never seen before. She also saw the slave-trading port, saw her countrymen being shipped of by the hundreds. Upon meeting with the governor, she was welcomed and given a residence for the duration of her stay.

When the time of negotiation came, Njinga found that all the governor was seated in a fancy chair while she was expected to sit on a mat on the floor in front of him. Not having any of it, Njinga motioned her maid to crouch for her to sit on her back – a gesture of power that made clear that she was not here to surrender but to negotiate on equal footing. And so it began. The Portuguese didn’t expect such a formidable opponent who spoke their language so well and thus they came to an agreement that actually benefited both sides: Ndongo was to be recognized as a sovereign state and all troops were to be called back. In return, they would be establishing trade routes with the Portuguese. Since that went so well, Njinga decided to stay a little longer and even converted to Christianity, hoping to strengthen the peace treaty even more. After staying for almost a year, she returned home.

Peace was shorter-lived than her stay at Luanda had been. In the same year the governor of Luanda was replaced and his successor didn’t care much for the treaty. He continued to raid Ndonga and the kingdom of course retaliated, Njinga fighting with her people. One year later, in 1924, King Ngola died. It is unclear how he died; if he committed suicide due to his military failures, or if his sister killed him after all. But however it happened, Njinga became Queen (after killing her nephew who could have objected her claim.) She was 43 years old.

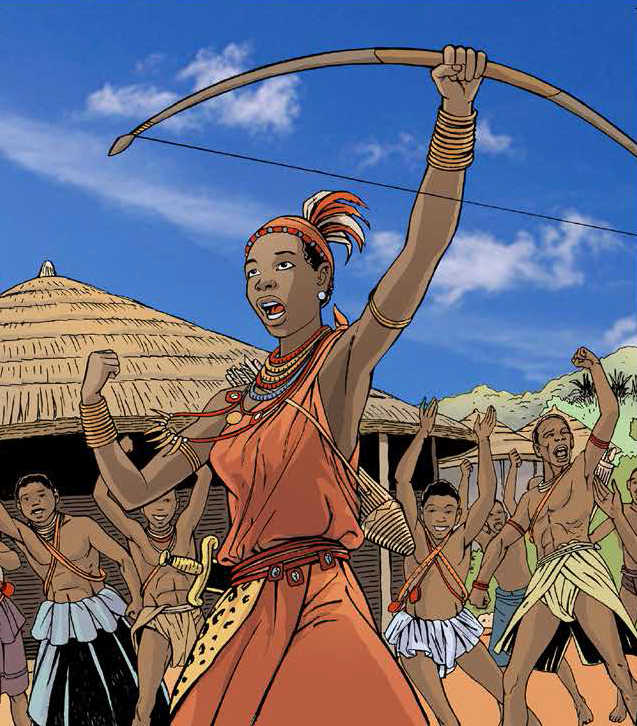

For two more years the people of Ndongo continued to defend their home against the onslaught of the Portuguese, but in 1629 they had to retreat. Partly due to the Portuguese threat and partly because there was an opposition against a female ruler, led by other aristocrats who had their eyes on the throne as well. Njinga took her people to Matamba, where she had once sought refuge from her brother’s wrath. Now she was there to take over the kingdom and by 1630 she had established her new capital. With this new power behind her, she returned to Ndongo and claimed her crown, uniting the kingdoms of Ndongo and Matamba under her rule.

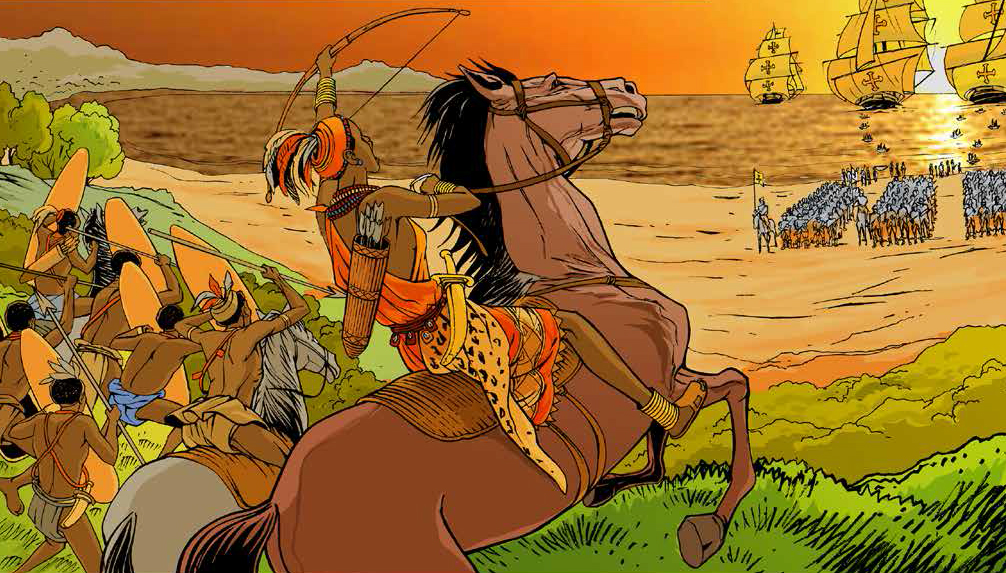

For more than ten years, Queen Njinga thwarted the Portuguese opposition, building alliances and cutting of trading routes, often charging into battle herself, leading her soldiers. Finally in 1641 she saw a chance to get rid of the Portuguese once and for all. The Dutch had just seized the city of Luanda and there was an opening to regain some of Ndongo’s former land. So she forged an alliance with the Dutch, moving her capital to Kavanga, which was in a territory that had been Northern Ndongo before the Portuguese arrived.

At first things looked good, Njinga scored some major victories and secured her new capital. However in 1646 an army of 20.000 Portuguese soldiers attacked the city and forced the Queen to retreat once more. With the help of her Dutch allies however she was able to come out victorious in the end only one year later.

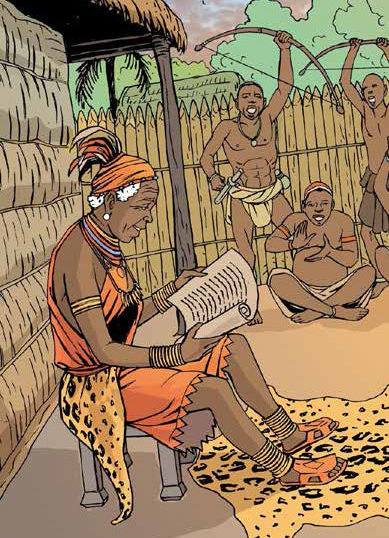

Unfortunately it was another short-lived victory. When the Portuguese regained Luanda, Njinga’s alliship with the Dutch ended and she once more retreated to her capital in Matamba. Continuing to be a thorn in the side of the colonizers for the next 20 years, employing guerilla tactics and spies, having trenches dug around her land and stocking up on supplies to prepare for the possibility of a siege. Furthermore she made her country a safe haven for all who needed to escape the colonizers.

And so she expanded her power even over her borders until finally in 1657 the Portuguese buckled. They didn’t know what to do in the face of this elderly woman who kept messing with their plans (Njinga was around 70 years old at this time.) And so they finally renounced their claims to Ndongo once and for all.

Now that the war was over, Njinga did all that she could to rebuild her nation, resettling former slaves and using Matamba’s strategic position to make it a major trading power. All the while she kept resisting attempts to either dethrone or murder her until she died peacefully in 1663 around the age of 82. Following her death the nation briefly descended into civil war, but after things had calmed down her legacy was continued.

Today she is called “The Mother of Angola” for laying the foundations for Angola’s resistance to colonialism way into 20th century until it finally became independent. She is remembered for her brilliant leadership, not only on the battlefield but also in diplomacy and and politics. As it is with important figures, there is a street named after her, there was a series of coins and in 2002 a statue of her was unveiled in Luanda. Particularly women consider her a role model as she laid the first foundations for equal rights between the sexes. And even though she had to fight to be accepted as a ruler, her female successors did not have to do so; of the 104 years that followed her death, 80 were ruled by queens.

Until today she remains a symbol of resistance and Angolan identity.

image credits:

1: “Queen Nzinga Mbande (Anna de Sousa Nzinga)” by Achille Devéria, printed by François Le Villain, published by Edward Bull, published by Edward Churton, after Unknown artist; hand-coloured lithograph, 1830s; NPG D34632 © National Portrait Gallery, London

2 – 5: from the UNESCO Series on Women in African History: “Pat Masioni” / “Njinga Mbandi, Queen of Ndongo and Matamba” / 978-92-3-200026-2 – licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO [6856] – Link

6: Queen Njinga’s Statue in Luanda, image from AfrikaNews – Link