Fatima al-Fihri – Paving the Way for Modern University Education

Today I want to tell you how a Muslim woman paved the way for higher education as we know it. This is the history of the world’s oldest, continually operating university as well as a story about determination and giving back to the community. Let me take you to 9th century North Africa where Fatima al-Fihri was born.

Around 800 AD in the Tunisian town of Kairouan, a merchant and his wife welcomed their first daughter into the world and named her Fatima. A second, Maryam, would follow soon. While it isn’t certain when the family became rich, it must have happened either before the girls were born or as they were growing up, as they enjoyed quite a few privileges.

They did receive a thorough education for example, both scientific and religious, and they were. Apart from this, not much is known about Fatima’s early life, except that she was devoutly religious, as was her sister. So we’re going to fast forward a little.

At some point she married and after an uprising in Kairouan the whole family decided to emigrate to Fez – a city in today’s Morocco on its way to becoming a bustling metropolis of the Islamic Golden Age – and settled in its west where many other people from their hometown were living aready. For now however, life wasn’t all that golden for Fatima. Shortly after her wedding her father died and soon after her new husband as well. There is no mention of her mother at all after this point, so I’m assuming she died before the family moved. So now Fatima and her sister were completely on their own in a new city.

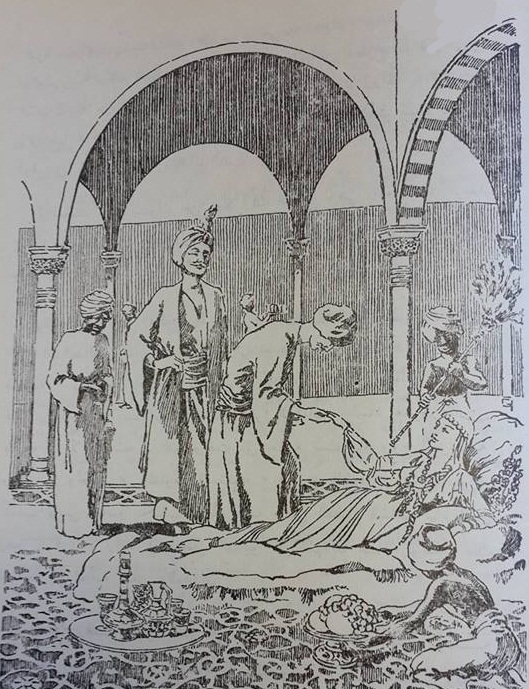

Being the only children to their parents however and with Fatima being a widow, the two women inherited quite a bit of money – most sources use the word “fortune.” But living modest lives, as was expected from Muslims, they didn’t really need that much and wouldn’t it be much more in Allah’s sense to give back to the community that so lovingly welcomed them? Maryam decided to buy a plot of land and supported the Andalusian immigrants of the city (who arrived prior to the wave from Kairouan) in building a mosque which they named Al-Andalus. It is still standing and one of the oldest landmarks of the old city center of Fez. Fatima too purchased land, near Maryam’s, however on her plot there was a mosque already which she tore down with the intention to rebuild it, but bigger and better!

It took 18 years until Fatima’s ambitious project was finished. She oversaw the whole building process and is said to have fasted for the final two years until it was completed. It was planned as a community hub, 1520 m² big with a courtyard with a fountain, enough room for many many books and space dedicated to learning. Although the mosque itself is beautifully intricate and extravagant, she made a point of keeping its construction modest, using only materials from the site. It was a remarkable process really: they dug deep into the earth to find different materials to use and rebuilt a stable foundation after. Finally in 859 AD it was done, the Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque (Al Kara-ween – named after her hometown) was complete. Fatima was the first to walk through its doors and pray.

In accordance with Muslim tradition, the mosque also functioned as a madrasa, a place of education and you might remember Fatima’s plan to include enough space for that purpose. She herself took an active part in learning too and attended lectures until old age. She also appears to have introduced certificates for completing studies in a certain subject, similar to our university degrees today! After seeing her mosque flourish and become a community hub, Fatima died around 880 AD, an old woman.

But her story doesn’t end here because it’s her legacy that truly made a difference in the long run. Around 30 years after Fatima’s death Al-Qarawiyyin became the Jama Masjid, the main mosque, of Fez. With time its library expanded and attracted scholars from all over the country and even from across its borders.

By the 12th century not only the Qur’an and Fiqh (Islamic Law) were taught there but also worldly subjects like grammar, medicine, mathematics and astronomy. It still wasn’t officially called a university, but it came pretty close to the system we have today. Many of the people who studied there became influential personalities in the Muslim world and beyond! And not only Muslims went there to learn and it is likely that it was at Al-Qarawiyyin where Pope Sylvester II (before he became pope) learned about arabic numerals which he then brought to the Western world. Even though it had been a hub for learning and scientific exchange, Al-Qarawiyyin didn’t receive its official university status until 1963.

Today the University of Al-Qarawiyyin is still standing and has been recognized as the oldest existing and continuously operating university in the world – it has been teaching for more than 1200 years! And even if Fatima did not really found it as an university, she built it as a place for learning. Thus she not only paved the way for significant progress in her country, but all over the world. Without her, our system of higher education would probably look way different. Just as Fatima wanted, Al-Qarawiyyin became a center of the community, making it better.

By the way: While the university itself is off-limits if you are not a student there, the library can be visited and of course the beautiful courtyard. So if you ever happen to be in Fez, you know where to go!

image credits:

1: “Fatima Al-Fihriyya Art Nouveau” by Nayzak on DeviantArt (cropped) – Link

2: “The oldest university of the world, Al Qarawiyine university in Fès” by User Abdel Hassouni in Wikimedia Commons, 2015 – Link

3: Fatima al-Fihri by Decue Wu for the Fiercely Female 2019 Calendar – Link

4: “University Al Quaraouiyine in Fès, Morocco” by User Medist in Wikimedia Commons, 2019 – Link