Yaa Asantewaa – Defender of the Golden Stool

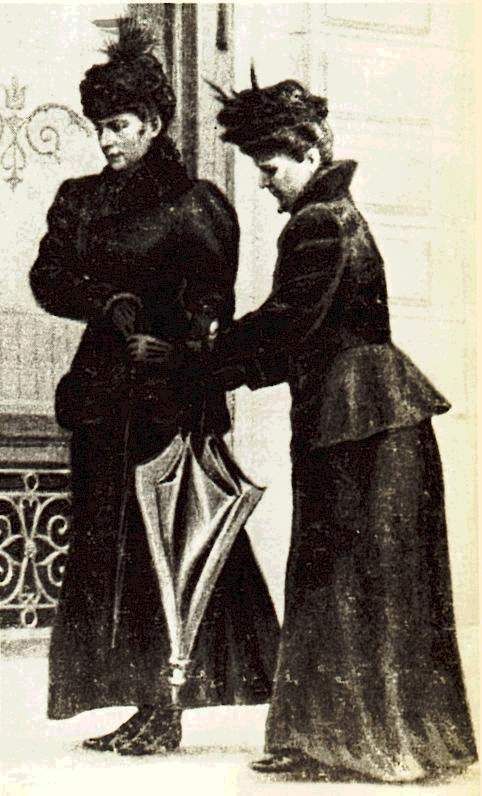

This is the story of a woman who defended her country against the British, refusing to stand down. Called “Africa’s Joan of Arc” by Western scholars, she commanded the entirety of the Ashanti forces in their final war against the colonialists. This is the story of Queen Mother Yaa Asantewaa.

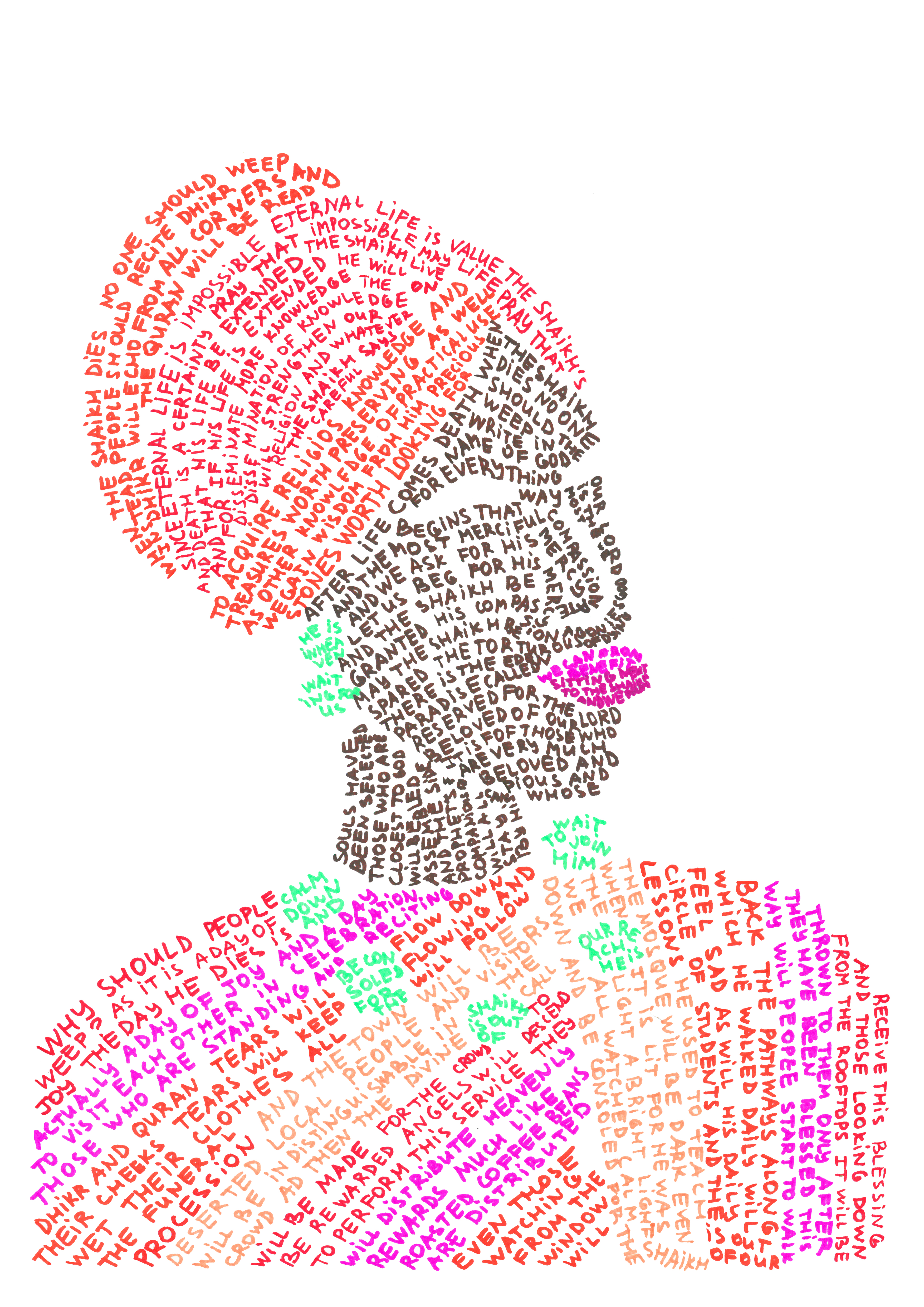

First, let me take you to the place and time where all of this happened: the Ashanti Kingdom in what is now Ghana. Unifying the individual village-states into a confederacy in 1701, its first king laid the foundation for what became one of the most sophisticated kingdoms in Africa. And of course there was some mythology behind it too. It was told that the Golden Stool, the symbol of the Ashanti throne, fell from the sky into the King’s lap, blessing his reign. Thus the Golden Stool became much more than just a throne – it became a symbol of the undying Ashanti spirit.

And now for the story of the woman who defended it. And it’s not just a myth!

Around 1840, Yaa Asantewaa was born as the oldest of the two royal children in the outskirts of Kumasi, the Ashanti capital, in a town that used to be called Edweso but today is named Ejisu. She grew to become a reputed farmer and cultivated crops on her own land until at one point she married a man from the capital. Following tradition she was but the first wife in a polygamous marriage, giving birth to one daughter. Meanwhile her brother ascended to the throne sometime in the 1880s, making her Queen Mother. You see, that title was inherited just as the royal ones were – and it held just as much influence. During his reign, Yaa witnessed the Ashanti confederacy go through crisis after crisis, war after war, and saw its stability waning. In the 1870s Kumasi was burned and ransacked, a tax was imposed by the British and a civil war was raging. And in the middle of all that her brother died. Making use of her position, Yaa nominated her grandson for the vacant position of chief and he was crowned in 1888.

He wasn’t able to enjoy his position for too long as in 1896 he was sent into exile to the Seychelles and the British demanded the utter surrender of his kingdom. Plus the Golden Stool would be nice. Four years they discussed and negotiated, hoping to a least get their king back for it. And just as the Ashanti chiefs were about to give in, Yaa’s thread of patience finally snapped. Refusing to pay her share of the taxes she gave a rallying speech about pride and courage and bravery. Still the chiefs were hesitant but she won them over quickly by announcing that, if the men are to scared to fight, the women will. And so in March 1900 a rebellion began.

Yaa became the first woman to lead and command the Ashanti forces and her leadership was so a skillful that the following war bears her name. Her first move was to turn her hometown into their base. With many of the men still hesitant to join the army, scared of the British military, she once again turned to the women. After convincing them to refuse to have sex with their husbands unless they fought for their country, most men were quick to join the war effort. For further encouragement, the women were to circle the city everyday, performing victory rituals and thus keeping morality high. For the first time in the Anglo-Ashanti wars, walls and palisades were built around cities and villages, successfully keeping the enemy at bay for the time being. She regained control of the capital by besieging the British fort within it, completely incapacitating its occupants and their allies on the outside. She proceeded to secure the city, deploying generals to monitor and protect strategic points. Yaa also employed psychological warfare against her adversaries, using the traditional talking drums to strike fear in their hearts whenever they heard the drums sing of battles won by the Ashanti.

In the end however the brave warriors were driven back by the British. Village by village, their strongholds were captured and finally Yaa herself was forced to surrender and followed her brother into exile to the Seychelles, accompanied by her generals. Their battle had lasted half a year. Her exile was set to last for 25 years, but Yaa would not see her home again. She died 21 years later.

The British however never got hold of the Golden Stool. It was hidden deep in the forests and only recovered by accident, when a group of labourers happened upon it in 1920. By then, even though they were technically annexed into the British Empire, the Ashanti still basically governed themselves and were not required to report to colonial authorities. And finally in 1957, their indepencence became official – the first African nation to achieve this. So despite her defeat in the end, Yaa Asantewaa’s resilience paved the way for her people’s de facto independence and succeeded in keeping the Golden Stool out of British hands.

image credits:

1: Asante. Stool (Dwa) – Museum Expedition 1922, Robert B. Woodward Memorial Fund – Brooklyn Museum (22.1695)

2: undated portrait of Yaa Asantewaa – Link

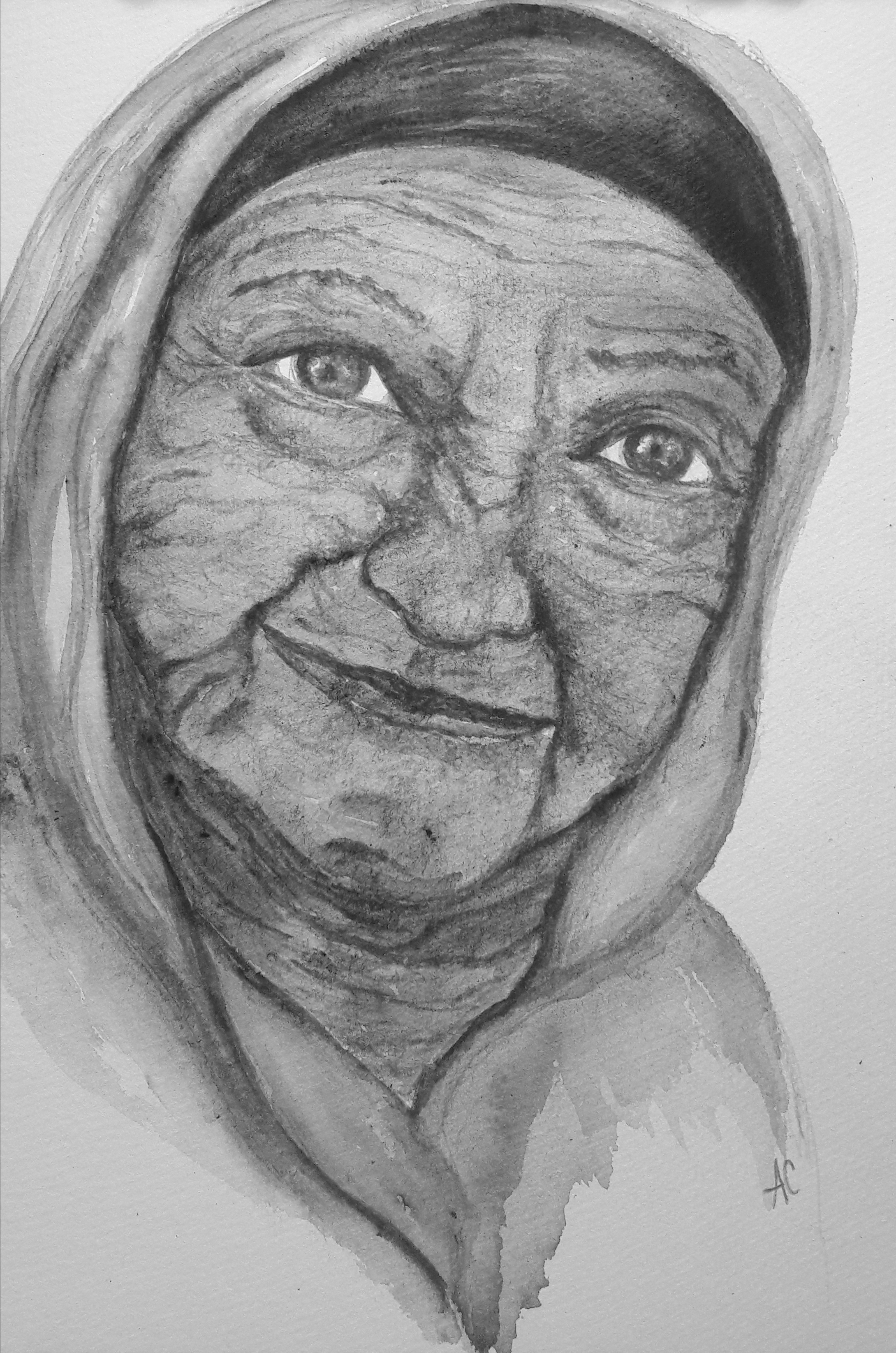

3: Yaa Asantewaa Museum – User Noahalorwu in Wikimedia Commons – Link

The Yaa Asantewaa Museum fell victim to a fire in 2004 and unfortunately has not been restored since. – Link