Kittie Smith – Refusing to Give Up

Katherine Smith, or Kittie for short, was nothing but an ordinary girl until both of her arms had to be amputated when she was only nine. But she would refuse to let this break her – or even shake her optimism.

In October 1882, she was born into a poor Chicago home with two older brothers and a younger sister to be born two years later. Often the kids went without food or proper clothes – a fact that was soon spotted by a local charity. So when she was nine, Kittie had the opportunity to attend a retreat in Whitley County where she was able to enjoy her childhood.

That happy time was cut short, when her mother suddenly died, making her the de facto head of the family and leaving the children in the care of their progressively alcoholic father. That same year, on Thanksgiving, her father drunkenly called for Kittie to prepare the food and as she didn’t obey (either she wasn’t quick enough or she refused trying to stand up for herself), he held her against the hot stove, badly burning her in the process. While her neck and chest got away with only minor burns, her arms were so severely injured that they had to be amputated. Later in life Kittie would claim that she lost her arms in an accident by her own fault, but court records highly suggest the opposite. Unfortunately Mr. Smith walked free as they couldn’t prove him guilty, but Kittie was taken from him nonetheless and placed in a home. That is when she was better, one year later, in 1892. The picture on the right is the only one showing her with her arms still intact and she “value[d] it very highly.” She is the girl on the far right.

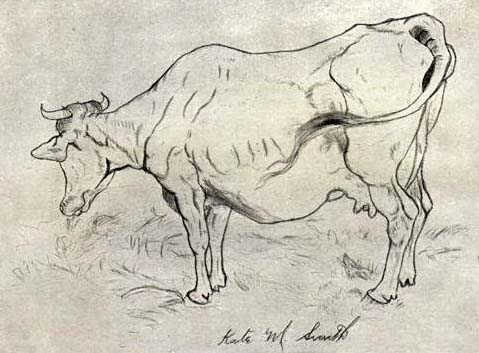

So now Kittie lived in the Home for Destitute and Crippled Children, as a ward of the Children’s Home Society of Illinois. There she came to the attention of one Dr. Gregg who set up an education fund in her favour and support poured in from far and wide. So specialists were hired and soon Kittie had learned to navigate life with her feet. Not only was she able to write and paint, but she played the piano and even did needlework! And when she moved to Wisconsin at age 14, the fund paid for her to attend public school. She didn’t take this for granted though and studiously completed her High School education.

But the time came she turned 21 and was no longer considered a child. This meant that she was no longer the responsibility of the Home Society. Furthermore her charity fund had run out. In the meantime her father had died, her brothers could hardly sustain themselves and the family had lost contact to her younger sister who had been adopted into another family. Kittie was on her own. Still she refused to give up. She began selling paintings and needlework done wit her feet, making a small living. With the support from friends she published a small magazine telling her life story which she distributed in the neighborhood. Included with the pamphlet came a return card with a slot for a quarter which the reader would only send if he found himself moved by the story – one of the first crowdfunding campaigns so to speak.

I don’t know if it was her tragic story, her optimism or the fact that she had forgiver her father long ago, but something about the young woman moved the people and by 1906 Kittie had crowdfunded more than $35.000 – all in quarters. And she put the money to good use, founding the Kittie Smith Company. Aiming to improve the living quality of disabled children, the company was created to help them overcome the obstacles created by their handicaps. To finance her endeavors, she now began selling her autobiography officially. Below you can see a few pages of the little book, showing her drawing and embroidery skills.

In 1913 women finally obtained the right to vote in Chicago. Kittie, now 31 years old, was the first to cast a ballot – using only her feet. Then it became relatively quiet around her until the 1930s when she joined the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus as a professional “Armless Wonder,” showcasing her remarkable skills.

She didn’t seem to like that line of work too much though, as soon she quietly left the spotlight for good. And that’s where her traces end. I like to imagine that she had quite a comfortable life though, managing her small business, painting and playing the piano.

You can read Kittie’s own account of her life and see more pictures here.

image credits: Sideshow World – Link