Katharina Henot – The Postmaster Who Was Burned As A Witch

Today I’d like you to meet Katharina Henot, Germany’s first female postmaster who was burned as a witch for economic and political reasons.

But let’s start at the beginning. She was born around 1570/80 to a wealthy family in Cologne (a city I live really close to by the way, it’s a local lady this time!), her mother coming from Dutch nobility. The family valued education and so most of her many siblings ended up with intellectual work, often in the church and one of her sisters joined the local convent. Originally being a silk merchant, father Henot managed to secure the job of reorganizing the country’s postal system, with Katharina and her husband (this is the only time her husband is mentioned anywhere) assisting him. Due to father Henot’s ambitious character however, his “supervisor” quickly got rid of him as soon as the job was done in 1603.

But the Henots fought. They fought for more than 20 years.

And finally, in 1623, they succeeded. Father Henot was reinstalled as postmaster of the city of Cologne. He had however reached the ripe age of 91 by that time, so Katharina took over (I suspect that her husband had died by that time). When he died two years later, the family was terrified to lose their licence again. And so they hid his passing, going as far as forging signatures when needed. For three months they managed, then they were found out. And her father’s adversary from before grabbed the opportunity. With plans to establish a central postal system, which would render the individual towns’ postmasters obsolete, he tried to take Katharina’s post from her. But she didn’t want to hear anything about it. And she went to court. Again.

And that’s when the rumours started. Nuns of the convent nearby (where not only her sister but also her daugher resided) reported being possessed, with Katharina being the one who had bewitched them. And even though she had always been giving generously to the church, her being a witch was soon the talk of the town. (This seems particularly odd to me because the nuns surely must have known her, being religious and having family members in the convent, but on with the story…)

You might have guessed it, Katharina did not take it silently. She wrote a letter to the archbishop, rejecting the accusations and urging him to inspect the circumstances at the convent. If he wouldn’t do that, she hoped that he would at least allow her to be judged by the clerical high court instead of the worldly one, which would most likely result in a mild punishment if she showed regret. These hopes were not to be fulfilled. Despite her knowing the archbishop personally and having lent him a big sum of money some time ago, he decided that her case was one for the worldly court – thus practically sealing her fate already.

Slowly running out of ideas, Katharina still did not give up. In consultation with her defense lawyer and supported by her brother, they planned a purgation process, which would basically allow her to swear herself free from the accusations (no, I don’t quite get that either). The formalities however took forever – apparently no one wanted to solve the situation quickly and above all, positively.

While still waiting for her purgation, Katharina was formally charged with witchcraft in early 1627. Two days later, she was arrested. Against regulations, she was denied medical aid, visitors and a proper defense in court. Her knowledge about law was dismissed, she wasn’t even told the exact charges. Her brother tried to have her released on bail, but was denied.

But even then Katharina did not break. Despite being crippled from torture and sick from the conditions in prison, she would not confess. She even managed to get out two letters to her brother, written with her left hand as her right had been paralyzed due to the torture. These letters chronicled her experiences in prison and once more declared her innocence, naming witnesses who could attest her. There was no answer.

On May 19, 1627 Katharina Henot was sentenced to death.

The accusations were “harmful magic, resulting in the death of five people, harmful magic in nature, feeding dispute, magical practices, divination (specifically with a divination rod) and sex with the devil.” These were backed by nothing more than the purportedly possessed nuns, the widespread rumors about her, the formal charge made by another nun and lastly the “confession” extracted from another alleged witch. A quick execution was pressed. And so, on the same day, she was hanged as a witch and her body burned (a little more merciful than the straight up burning).

This whole farce of a court is especially interesting: usually a witch could not be sentenced to death until she confessed – which was usually achieved with torture but since Katharina never confessed, this whole process is so wrong. She even declared her innocence one last time on the way to the execution site for heaven’s sake.

Her brother Hartger seemed to have had the same line of thought, as he chose to resign from his religious duties and asked for the trial records. His request granted at first, he ended up with only a few pages which did not give any new indication. The reasons why he was denied access to the papers are unknown, as is the true reason behind this odd witch hunt – the records did not survive the tooth of time.

It doesn’t end all bad though:

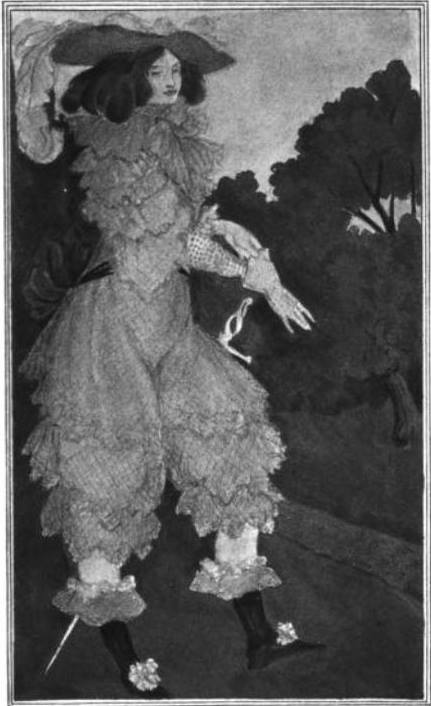

Many hundred years after her death, she is not forgotten in the city: her statue adorns Cologne’s town hall (1st picture: created by one of her descendants, Marianne Lüdicke, in 1988) and a street as well as a school are named in her honor. There’s even a movie (2nd picture: still from the movie “Die Hexe von Köln” from 1989 with Marita Breuer playing Katharina)!

But most importantly, in 2011 Katharina’s descendents achieved her official rehabilitation (and that of 37 other falsely convicted “witches,” male and female) – unfortunately almost 400 years to late. Still, I imagine she would appreciate it.

image credits:

statue: © Raimond Spekking / movie still: “Die Hexe von Köln,” 1989 – TV Spielfilm archive