Lady Emma Hamilton – More Than Just A Muse

This week I would like you to meet Lady Emma Hamilton, although you might know her already as the muse of several famous paintings (notably by George Romney, see picture). But there is a lot more to her than her pretty face and that’s what this post will be all about.

Born 1765 in the English town of Ness, her original name was Amy Lyon. Not much is known about her early life, but that she was earning her living as a maid. Her next job was dancing at the “Temple of Health,” an establishment lead by a quack doctor, where she met her first lover when she was 15. He wasn’t a very kind guy and ditched her when she became pregnant with his child. She had however formed a friendship with Charles Greville, Earl of Warwick, who was not a very interesting person and double her age, but kind and sincere.

So she decided to become the mistress of Greville, who after all was of noble blood and a nice man – and smitten with her. He accepted her into his London home under the condition that she severed all ties to her former life, as it had been a tumultuous and at times scandalous one, that he did not want associated with his person, being of nobility and all.

And so she did, adopting the new name of Emma Hart, and moving into Greville’s appartement in 1782. She was taught noble manners, had writing and singing lessons and became interested in literature and the arts. She was also introduced to famous painter George Romney, as her lover wanted to have her portrait painted.

Romney fell in love with Emma too, on an intellectual, artistic level, so she became his muse and the subject of many of his paintings. He never had her sit in any indiscreet poses though, even if he had her model nude, showing how much respect he had for her. Through these paintings, she became quite famous in London’s society, being witty and smart on top of her beauty and elegance. And quite a few painters decided to portray her in their works, her ability to adapt a variety of roles attracting them. (see picture, by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun)

In the meantime, just one year after she had moved in, Greville’s love for Emma diminished and he hoped to find a rich heiress to marry, helping his measly financial situation. The relationship with his mistress however posed a threat to these goals, no potential bride would accept him when he openly lived with another woman.

Luckily it was exactly then that his uncle Sir William Hamilton came to visit him from Naples – and fell head over heels for Emma. She remained faithful to Greville however and did not return his avances.

In 1786, Emma departed for Naples nonetheless – an only six-month stay, Greville had promised, while he was away on business in Scotland. This was nothing but a scheme though and all Greville wanted was to usher Emma off to become Hamilton’s mistress, so that he could marry his sugar mama. At first she felt homesick, but Hamilton proved himself a true gentleman who shared many of her interests and introduced her to Naples’ high society. So she grew to like life in the city, learned Italian and French and was fascinated by Hamilton’s vulcanic research. Not too much later though, she realized she was supposed to stay in Naples as her host’s mistress. She wrote many letters to Greville, assuring him of her love and that she felt nothing but friendship for his uncle. He coldly replied she was to do as his uncle wished. There was nothing else she could do, so she accepted Hamilton, who was 35 years her senior, as her lover.

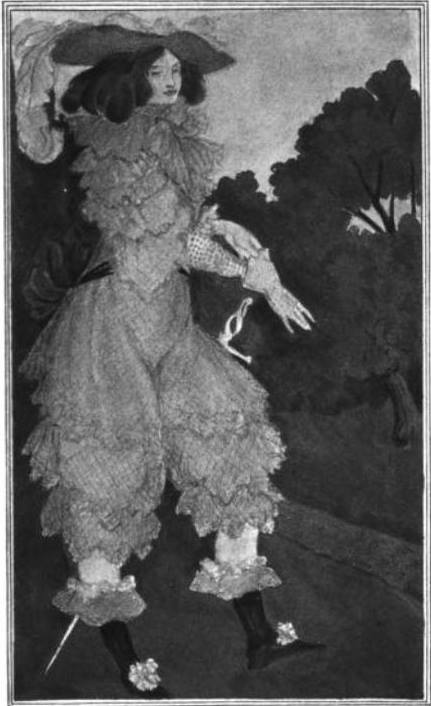

Making the best of her situation, Emma began to live her artistic ideas, starting to exhibit “living pictures” for her guests (see picture). Using minimal requisites, she managed to captivate her audience, making these kind of performances an accepted art form. With these “attitudes,” as she called them, as well as with her singing voice she was soon known throughout Europe – basically the Marilyn Monroe of her time. She even managed to win over members of the court, who had originally disdained “the courtesan.”

In 1790 Sir Hamilton decided to legalize their relationship. Greville was shocked (heh!). This marriage could prove fatal to Hamilton’s position as British ambassador though, so they travelled to London to ask the king for permission. Emma used this trip to reconnect with many of her former acquaintances, including George Romney who created several more paintings of her. Although Queen Charlotte refused to meet “the mistress,” King George III gave his blessing in secret. On September 6th, 1791 they were married in Marylebone Church, where Emma, now Lady Hamilton, signed the register with “Amy Lyon,” her birth name – a scandal in British aristocracy.

On their way back home, they came through revolution-torn Paris, where they talked with Marie Antoinette and received a confidential letter to the Queen’s sister in Naples, Queen Maria Carolina. Emma delivered the letter, a meeting that resulted in a long and close friendship with the Neapolitan Queen – there were even rumours of a lesbian relationship (but as much as I love my historic lesbians, I highly doubt that and consider it propaganda, there were a shitton of critics).

With this friendship Emma’s role became a more and more political one, acting as middlewoman for correspondence and translating delicate documents. That’s how she met Admiral Nelson, who returned from battle wounded but victorious. Emma nursed him back to health and eventually they fell in love. This affair was entirely tolerated by the elderly Sir Hamilton, who had nothing but respect for the Admiral – a feeling that was mutual.

When the French were advancing into the kingdom of Naples. The Hamiltons fled with the Queen’s household on Nelsons ships to Palermo, Sicily. The Neapolitan territory was recovered but the Hamilton estate destroyed, so the couple did not return home. Instead they embarked on a sea journey with Nelson where Emma spent the nights with the Admiral, eventually becoming pregnant. Finally back in England, Emma now met Nelson’s wife Fanny for the first time in late 1800. Only a few months later, Fanny ended the marriage as Nelson was not willing to give up Emma, which resulted in him moving in with the Hamiltons. Society did not approve.

After Emma gave birth to Nelson’s daughter, who was named Horatia, the triad moved to Merton Place, a residence in the outskirts of London in 1801. Two years later Sir Hamilton died with both Emma and Nelson holding his hands. Unfortunately Greville (remember him?) was appointed the sole heir of his uncle’s estates, the price for Emma years ago. She only got a small yearly pension.

Even though Nelson was a sea frequently, the couple enjoyed their times together and Emma encouraged him in fulfilling his duty even if she probably didn’t like seeing him that seldomly. In 1805, they were married in St. Paul’s Cathedral just before his final departure. While the Battle of Trafalgar was won by the British, it was Nelson’t final fight. He was struck by a bullet and died immediately. Neither her nor his ex-wife Fanny were invited to his burial. She did inherit Merton Place and got a yearly pension, but Nelsons final wish that she be supported by the state of Naples for her diplomatic deeds was rejected.

In the last decade of her life, Emma’s health and wealth deteriorated, a huge contribution being her ensuing alcoholism. Her pensions were often paid to late and didn’t suffice to pay her considerable debt (she had never been good with money). Finally she was forced to sell her home to pay off a part of her creditors and placed in a small barrack under house arrest with her daughter. In the end the small family fled to France (the irony) where Emma died in Calais in 1815.

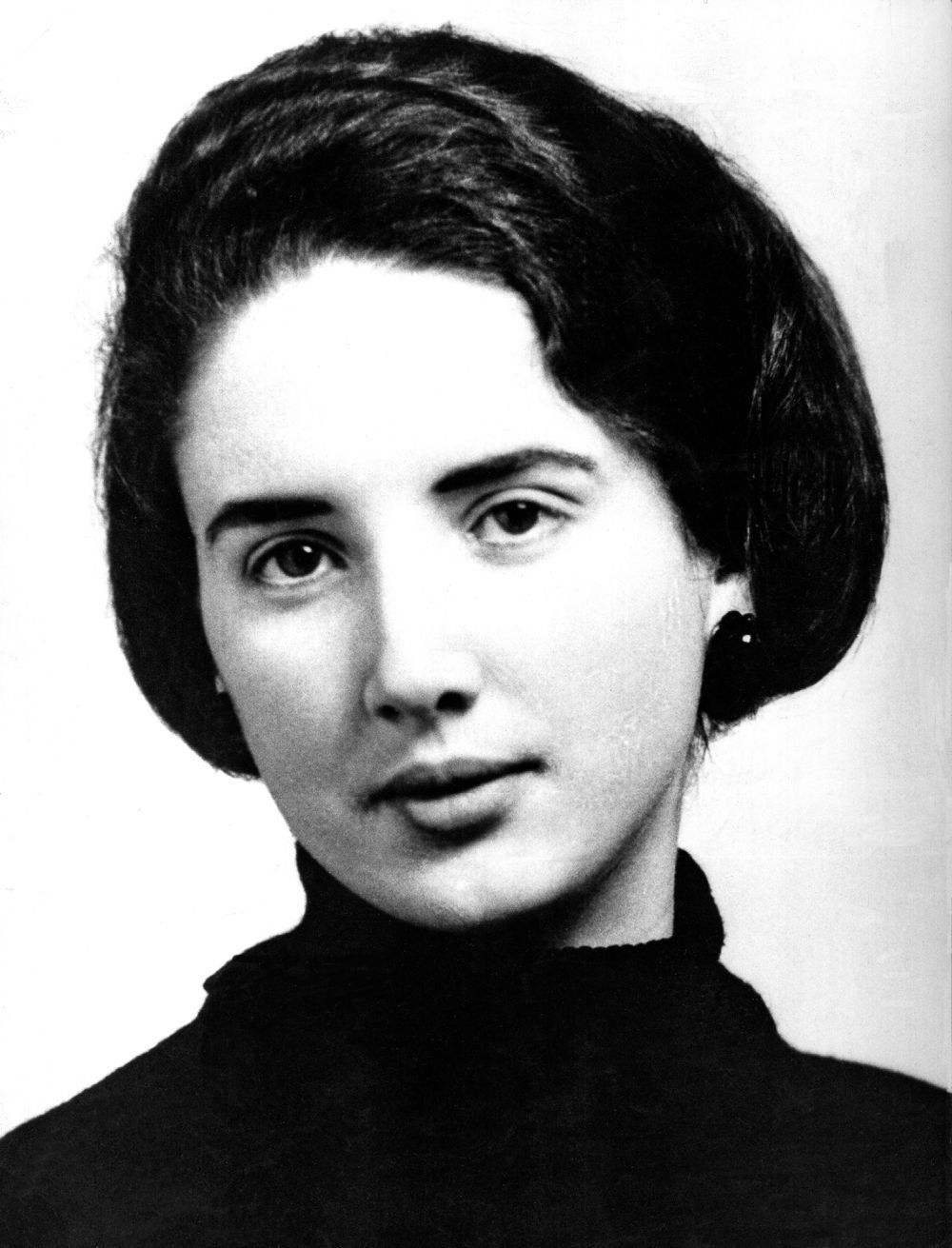

The picture on the left is a pastel owned by Nelson, painted around 1800.

A tumultuous and scandalous life for sure and a woman who was much more than just a pretty face, just trying to find happiness and being taken along by the flow of life. But forever immortal in a multitude of paintings.

image credits:

1: “Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton as Circe” by George Romney, ca. 1782 – © National Trust, Waddesdon Manor (104.1995)

2: “Lady Hamilton as a Bacchante” by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, ca. 1790 – © Lady Lever Art Gallery (WHL 712)

3: from “Drawings Faithfully copied From Nature at Naples and with permission dedicated To the Right Honourable Sir William Hamilton” by Friedrich Rehberg – Link

4: “Emma, Lady Hamilton”, by Johann Heinrich Schmidt, 1800 – © National Maritime Museum Collections (PAJ3940)